Looking for information about other Dental Topics?

Full Website Index• Animated-Teeth.com •

Evaluating and preparing the jawbone for dental implant placement.

A preoperative evaluation is needed before dental implant placement can be recommended.

While dental implants can offer a transformative solution for replacing missing teeth, their success is highly dependent on the health and suitability of the jawbone in the area of the implant site.

What kind of preliminary assessment is required?

Before a patient’s treatment can begin their dentist must evaluate the bone quantity and quality at the proposed surgical site to ensure that it can adequately support the implant and withstand the level of stress it will be subjected to. Equally important are the characteristics of the soft tissues (gums) that lie over the bone.

In cases where either is found to be lacking, a preparatory procedure such as bone or soft-tissue grafting is often needed to improve the site’s characteristics before the patient’s implant can be placed.

What specific factors are assessed to ensure implant suitability?

Key factors that will require evaluation include bone density, volume, and the type of gum tissue that lies over the jawbone. The site’s proximity to anatomical structures and any conditions that could hinder healing or osseointegration (the process where the implant integrates with the jawbone) must be identified too.

Diagnostic imaging (taking X-rays) will play an important role in making many of these determinations. This guide also explains how these and other methods are used to evaluate and prepare the jawbone for implant placement to ensure that a foundation that promotes a successful treatment outcome and long-term patient satisfaction exists.

If you have a special interest in a specific aspect of our coverage, use these links.

- Assessing bone suitability for an implant.

- X-ray and imaging techniques used to evaluate the jawbone.

- Factors and conditions that may disqualify implant sites.

- Soft-tissue considerations for implants.

- Solutions for implant site deficiencies.

Techniques dentists use to assess bone quality and quantity.

Because the long-term success of a dental implant is so dependent on the suitability of the bone in the region in which it’s been placed, before laying plans for a patient’s procedure the treating dentist must first:

- Evaluate the quantity (bone volume) and quality (bone density and architecture) of the tissue in the region of the planned implant.

- Ensure that the planned location for the implant in the jawbone is distant enough from neighboring anatomical structures (teeth, nerves, sinuses, etc…).

- Determine that there is no pathology associated with the area that will interfere with the successful outcome (placement, healing and osseointegration) of the device.

Methods dentists use to evaluate implant sites.

When passing judgment on the above factors, the dentist’s method of examination will need to be twofold.

- One aspect will involve routine clinical techniques like visualization, palpation (touching, feeling), and measuring the jawbones.

- The other will involve the use of dental radiographs (X-rays).

What type of X-rays will be needed?

In some cases, a simple combination of the following radiographic techniques will be satisfactory for planning and performing a patient’s procedure.

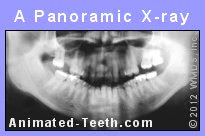

1) A panoramic X-ray evaluation – This is a single large radiograph that shows both of the patient’s jaws and all of their teeth (see picture).

The American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology (AAOMR) considers a conventional panoramic evaluation to be the imaging modality of choice for initially evaluating a patient for a dental implant. (Tyndall 2012)

2) Supplementary periapical radiographs – These small X-rays (the kind most often taken in a dentist’s office) are used to examine just small areas at a time (like those associated with just one or a few teeth) and may be needed to supplement or clarify what’s noticed on the panoramic evaluation.

▲ Section references – Tyndall

The role of 3D X-ray imaging in implant dentistry.

In other cases, the dentist may feel that the additional, more-detailed level of information that only 3D X-ray imaging (3D computerized tomography, 3D CT) can provide is needed. In dentistry, the most frequently used type of 3D imaging is Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT).

Due to the cost of this equipment, it’s more common for a dental specialist (i.e. oral surgeon) to have 3D capabilities in their office rather than a general dentist. However, a patient can be referred for this type of imaging if needed.

Important considerations when using 3D imaging.

Beyond the added expense it involves, 3D imaging also exposes the patient to added radiation. And for both of these reasons, it should never be considered just a routinely included part of a patient’s treatment. The need for it must be justified. This position is endorsed by the AAOMR (Tyndall 2012).

Advantages of 3d imaging for pre-implant evaluation.

There is no question that the 3D nature of a Cone Beam scan can provide useful information that otherwise would be impossible to collect.

- Using CBCT cross-sectional imaging, a dentist can accurately determine the volume (height, width, shape) of the jawbone in the area of the planned implant. (2D imaging isn’t able to provide jawbone width, and therefore detailed shape and volume, information.)

- CBCT imaging allows the dentist to determine how closely different structures (teeth, nerves, sinuses, etc…) lie to the area of the proposed implant.

Having this information can help to prevent procedural complications. And in areas where the available bone is deficient, having this information helps the dentist understand the full extent of the bone graft that will be needed. (Such as a sinus lift.)

- The digital file created during a CBCT scan can be used to design and print (fabricate) surgical guides.

These are temporary appliances used during the implant procedure that help a dentist to accurately orient the placement of the device (position, angle, depth, etc…) in the jawbone.

Key factors dentists analyze at implant sites during their evaluation.

1) Jawbone quantity and quality.

The dentist must determine that there’s an adequate quantity of bone in the region of the planned implant and that it’s of sufficient quality.

- Making this determination will involve evaluating the overall shape of the bone (both width and height).

- The architecture of the bone’s internal honeycomb-like structure in the region of the placement site (including the size and orientation of the spaces) must be evaluated too.

- An estimation of the bone’s density (bone mineral content) must be made too. Within the same patient, and simply due to the biological nature of each respective jawbone, this can generally be expected to be lower for maxillary (upper) jaw sites as opposed to mandibular (lower) ones.

Categorizing bone density and quality.

While methods of making a direct evaluation of bone density do exist, a dentist usually estimates implant-site suitability based on evidence revealed by X-rays, especially CTBT scans. CBCT scans provide a series of cross-sectional views of the jaw that enable the visualization of bone density variations (as represented by the degree of translucency or opaqueness shown on the image).

These findings are then categorized according to the Lekholm and Zarb system, which uses four “types” to classify the internal structure and density of the jawbone.

The Lekholm and Zarb classification system.

- Type 1 – Dense cortical bone exists throughout the jaw. This offers high strength characteristics but low vascularity, which can slow healing.

- Type 2 – This category offers the most ideal situation. A thick cortical (outside) jawbone layer with dense trabecular (internal) bone. This provides a balance of good strength and good healing potential.

- Type 3 – This category of bone features a thinner cortical bone layer with moderately dense trabecular bone, which may require careful implant placement.

- Type 4 – Sites placed into this category consist primarily of low-density trabecular bone with minimal cortical bone, making it the least suitable category for implants without additional preparation like grafting.

2) Bone conditions/factors that may disqualify jaws for implant placement.

A dentist’s evaluation of their patient’s jawbone may discover characteristics or reasons that make it unsuitable for their planned implant, at least initially.

a) The presence of infection.

Especially in cases where an existing tooth occupies the location where an implant will be placed, the dentist will evaluate the tooth and its surrounding tissues for evidence of infection.

- Generally speaking, and especially in the case of elective surgeries like implant placement, a dentist will be hesitant to perform the patient’s procedure in an area showing signs of active (acute phases of) infection, like situations where swelling is involved.

Doing so might complicate performing the procedure, possibly aid in spreading the infection, or hinder the healing process that follows.

So if signs of active infection are discovered, the dentist will place a priority on limiting its extent (bringing it under control) before proceeding with any surgical steps.

- If immediate implant placement is planned (a situation involving the removal of the existing tooth and then immediately placing the implant in the fresh extraction site), the presence of a limited infection associated with the existing tooth may or may not prove to be a contraindication.

Based on their review of published research, the authors of some papers (Marconcini 2013, Chrcanovic 2015) have concluded that the presence of an infection (either root canal or gum disease-related) may be a manageable condition and therefore doesn’t necessarily contraindicate the immediate placement of dental implants as long as appropriate pre and post-surgical steps are taken.

Of course, only the treating dentist can determine if placing an immediate implant under these conditions makes an appropriate option for their patient or not.

- Extraction of the infected tooth first, followed by a 4 to 6-month healing period, has been the approach followed historically to manage this situation.

▲ Section references – Marconcini, Chrcanovic

b) Excessive bone resorption.

Bone resorption (bone loss or atrophy) is a natural process that takes place following a tooth extraction. And if enough loss has taken place, there may not be enough bone quantity in which to place an implant (at least not without doing a grafting procedure first, see below).

Details.

This type of defect is often most noticeable in regions where multiple teeth have been removed, especially if several years previously. The bone in the area typically has a sunken-in appearance.

The magnitude of post-extraction bone loss can be as much as 40 to 60 percent within the first three years following the tooth’s removal. Beyond that point, the rate of loss characteristically slows down substantially.

The cause of the resorption is typically attributed to disuse atrophy (decreased blood supply, localized inflammation and/or unfavorable pressure from a dental appliance, such as a partial or full denture).

c) Bone damage due to disease.

In other cases, a patient’s bone deficiency may be attributed to a dental condition, such as bone loss caused by advanced periodontal disease (gum disease).

As a result of this condition, significant amounts of bone may be lost from around the person’s teeth,

to the point where if they are extracted there may be an inadequate quantity of bone in which to place an implant.

d) Bone loss due to previous surgery or trauma.

In some cases, the bone deficiency that’s identified may be due to a previous surgical procedure (like a difficult tooth extraction or the removal of a cyst or tumor) that has resulted in the removal of a significant volume of bone. Traumatic injury to the jawbone may also result in a deficit of bone tissue in the region of the proposed surgical site.

e) The presence of bone pathology.

The dentist must search for evidence of pathology within the jawbone, such as tumors and cysts.

Additionally, impacted teeth and tooth root fragments (remnants of past extractions) need to be identified and removed as the dentist feels it’s needed.

f) Conflicts with anatomical structures.

The location of anatomical structures, such as sinuses, nerves, blood vessels and the roots of adjacent teeth must be identified.

This is important because implants must be placed so they are suitably distant from these objects.

Nearby anatomical structures must not be impinged by implant placement.

3) Soft-tissue considerations for implant sites.

A portion of the dentist’s clinical examination must also involve an evaluation of the soft tissues of the patient’s mouth. They must be healthy and free of pathology. There must also be an adequate quantity and quality of tissue at the proposed surgical site.

Tissue characteristics needed at an implant site.

- An adequate zone of healthy keratinized gingiva (“attached gingiva,” like the tightly bound gum tissue that surrounds your teeth), is needed. This type of tissue helps to establish a protective seal around the implant that helps to reduce its risk of bacterial invasion and peri-implant diseases.

Having an adequate amount of keratinized tissue also aids in maintaining oral hygiene and the prevention of inflammation due to the way its contours around the implant help to prevent food impaction and facilitate effective cleaning.

- In highly visible areas (like replacement front teeth), the contours of the gum tissue that surrounds the implant play a vital role in the final aesthetics of the artificial tooth that’s placed and therefore how natural it looks.

Solutions for addressing implant site deficiencies.

Since the preoperative conditions at the implant site play such an important role in contributing to the restoration’s long-term success, when deficiencies are found the dentist must take steps to remedy them.

a) Bone grafting may be necessary before an implant can be placed.

Bone grafting provides a way for the dentist to improve the quantity or quality of bone tissue that exists at an implant site. The grafting that’s placed might be an autograft (bone tissue harvested from the patient), an allograft (tissue taken from a donor), a xenograft (bone harvested from animals), or even some type of synthetic material. Each offers its own advantages.

An adequate amount of bone must exist for an implant.

In this case, bone grafting will be needed.

Bone grafting procedures.

Grafting procedures are typically performed as a separate procedure. And following the procedure, a healing period (usually 4 to 8 months) is typically required before the implant can then be placed.

We discuss one such grafting procedure termed a Sinus Lift here. It’s frequently performed in association with placing implants to replace upper back teeth (like maxillary molars). Lower (mandibular) implant sites are sometimes lacking in adequate bone width and therefore ridge-expansion grafting is needed.

b) Soft-tissue grafting may be required too.

In cases where the implant site’s gum tissue is determined to be deficient, some type of soft-tissue grafting procedure, such as a free gingival graft or connective tissue graft, may be needed. These procedures can enhance the quantity and quality of the tissue at the proposed surgical site so to improve its functional success and also ensure an optimal aesthetic outcome.

Recent advancements, such as platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and laser-assisted grafting techniques, have further refined these procedures and offer a less-invasive surgical option and less-eventful healing experience for the patient.

Looking for more information?

Beyond just the suitability of your jawbone for an implant, there are additional patient factors that must be considered too. We discuss them here: Who makes a good candidate for a dental implant? Jump

Or, if you’re looking for other information, scroll on down a few lines to see our ‘What’s Next?’ menu. It lists other pages on our website that discuss tooth implant issues. Thanks for visiting.

Last reviewed: December 14, 2024

Author: Paul Cotner, DMD — retired dentist.

Published by: WMDS, Inc. — owner of Animated-Teeth.com.

Educational information only — not a substitute for professional dental care.

Page references sources:

Chrcanovic BR, et al. Immediate placement of implants into infected sites: a systematic review.

Marconcini S, et al. Immediate implant placement in infected sites: a case series.

Tyndall DA, et al. Position statement of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology on selection criteria for the use of radiology in dental implantology with emphasis on cone beam computed tomography.

All reference sources for topic Dental Implants.

Comments.

This section contains comments submitted in previous years. Many have been edited so to limit their scope to subjects discussed on this page.

Comment –

Is cone beam X-ray necessary?

My expenses just keep piling up.

K.V.

Reply –

Really, only a dentist to whom you went to for a second opinion would be able to answer this question.

From the patient’s view, we get that some services that are performed often seem just to be profit centers, or utilized just to help to pay for expensive equipment that has been purchased.

At the same time, the dentist no doubt wants everything about the procedure to be successful (and clearly 3D imaging does provide a higher level of information). And legally they are obligated to practice dentistry at the same level as other practitioners (so if most dentists would have used cone beam imaging for your case and your dentist didn’t and a complication arose …).

Per our AAOMR references above, theoretically it’s expected that a dentist will initially evaluate their patient using more conventional types of radiographic exam (panoramic X-ray) and then make a decision for 3D imaging based on that.

It seems reasonable that a dentist would share with their patient what they see on that X-ray that suggests that CBCT imaging is indicated. (While we didn’t mention and as you seem to suspect, yes many implants are placed without the assistance of CBCT radiography.)

Staff Dentist