Tooth and bone fragments (after tooth extraction). –

Postoperative complication – The appearance of tooth or bone fragments in your gum tissue after a tooth extraction.

Table of contents –- Post-extraction tooth shards and bone fragments.

- Fragment identification and pictures.

- Types of fragments (with pictures) – Pieces of tooth / Root tips / Remnants of dental restorations / Bone fragments, spicules, spurs, bony flakes.

- How common are they? – Incidence rates.

- Appearance in the mouth.

- Distinguishing tooth shards from bone fragments.

- Biological considerations.

- Treatment and removal.

- Treatment provided by your dentist – The steps. Will an anesthetic be needed?

- DIY / At-home fragment removal – The steps.

- Healing after removing.

- Complications associated with larger fragments.

- Bone fragments not associated with tooth extraction.

- Other ways to learn.

- This page’s highlights as a video.

- Types of fragments (with pictures) – Pieces of tooth / Root tips / Remnants of dental restorations / Bone fragments, spicules, spurs, bony flakes.

- How common are they? – Incidence rates.

- Appearance in the mouth.

- Distinguishing tooth shards from bone fragments.

- Treatment provided by your dentist – The steps. Will an anesthetic be needed?

- DIY / At-home fragment removal – The steps.

- Healing after removing.

- Complications associated with larger fragments.

- Bone fragments not associated with tooth extraction.

- This page’s highlights as a video.

A common scenario.

One postoperative complication sometimes associated with oral surgery procedures is that of discovering one or more small hard, often sharp, fragments (splinters, shards, slithers, spurs, chips) of tooth or bone that have worked their way to the surface of your surgical site and are now sticking partway out of your gums.

A common timeline.

- After having had your surgical procedure, the healing of your wound has progressed normally and uneventfully.

- Then, after some days or weeks, your tongue suddenly discovers a tiny hard object sticking out of your gums.

- What you notice may feel like a small rounded lump or a sharp-edged splinter.

This scenario is more likely to take place after relatively more difficult or traumatic oral surgery procedures that have involved bone tissue. This includes surgical tooth extractions (like the type of procedure used to remove impacted wisdom teeth) and alveoloplasty (jawbone ridge shaping and contouring) but can also follow routine (“simple”) tooth extractions.

What you need to know.

This page (and its accompanying video) explains why these hard bits and shards (tooth fragments / bone sequestra) form, and provides pictures of what they look like.

It also outlines how they are usually removed, either by your dentist or, in the case of the smallest splinters or spurs, on your own at home as self-treatment. We also include a discussion about how cases involving larger and/or multiple fragments are managed by dentists and oral surgeons.

This page’s highlights as a video –

Subscribe to our YouTube channel.

Types of hard objects that may be discovered in healing extraction sites.

- Pieces of broken tooth.

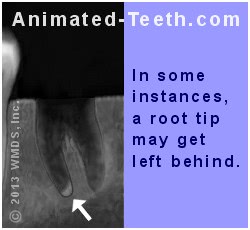

- Broken off root tips.

- Bits of broken filling material.

- Fragments of broken bone.

- Pieces of dead bone tissue (sequestra).

What types of fragments are involved?

- Tooth pieces / Root tips. – It’s not terribly uncommon for a tooth to break or splinter during its extraction process. For example, root fracture is the most common intraoperative complication and is estimated to occur in 9 to 20% of cases. (Ahel)

Or, before a tooth does break, a dentist may strategically decide to cut it up into parts. This is referred to as “sectioning” a tooth The rationale. and doing so can make it easier to get it out.

Whatever the case, if bits or shards have been created, some of them may get left behind after the extraction process has been completed.

- Remnants of the tooth’s dental restoration. – The forces used to remove a tooth may dislodge or break its filling. If so, they may find their way into the empty socket and get left behind.

- Bone fragments, spurs, spicules, bony flakes. – Two different scenarios may be involved when these types of objects form.

1) Broken bone – Bits of a tooth’s bony socket may break off during the extraction process.

2) Damaged bone – Bone is living tissue, and if it’s traumatized enough during the extraction process aspects of this damaged bone may die (see below). These types of fragments are called “sequestrum” (singular) or “sequestra” (plural).

▲ Section references – Ahel, Sigron

Is it normal to have fragments appear after a tooth extraction?

No, it’s not “normal” to discover pieces of bone or tooth coming to the surface of your extraction site during its healing process (the vast majority of extractions are not accompanied by this complication). But at the same time, having this experience certainly isn’t uncommon.

It is a phenomenon that’s more likely to be associated with comparatively more difficult extractions. But even then, you don’t have to expect that it will occur.

Occurrence statistics.

- A study by Sigron placed the incidence rate of sequestra formation (bone fragments) following the surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth at 0.32% of cases.

(Since this can be one of the most challenging types of tooth extractions, it might be expected that experiencing fragments would be comparatively more likely with this type of procedure.)

- In regard to routine extractions, we could find no statistics to report.

Your potential for experiencing this phenomenon would be multifactorial, with issues such as the skill of your dentist, the extraction process used, your age, and the quality of bone all being considerations.

▲ Section references – Ahel, Sigron

What do the fragments look like?

You may be able to visualize the spur of bone or shard of tooth sticking out through your gums. But if you can’t, don’t be too surprised.

- The location of the protruding bit may be such that it’s essentially impossible to view it without aid (such as the good light source and small oral hand mirror that your dentist has to use).

- The sharpness or irritation that your tongue feels and interprets as being caused by something large may in reality be caused by an object so small that it’s difficult to visualize.

How the lesion looks in your mouth.

In response to the presence of the (foreign) object, the soft tissues that surround the fragment will characteristically show signs of redness (erythema), and maybe even some minor, very localized level of swelling (edema). The area may be tender to touch.

In some cases, an ulceration may form, especially when larger bone fragments are involved. These lesions typically display a whitish surface membrane surrounding a hard center section of exposed bone.

Post-extraction bone sequestrum (spicule, spur) and tooth fragment.

1) Pieces of tooth will be smooth and rounded on one side and sharp-edged on the other. 2) All sides of a bone spur will be irregular.

Inspecting the fragment.

- Bone bits (sequestra / spicules / spurs / fragments) – As our picture illustrates, these items are usually very irregular in shape, with rounded or sharp edges. Their color is usually light tan to white. Their surface will look smooth but lobulated (not perfectly flat but bumpy).

- Tooth fragments – These slivers can be very shard-like (pointed, sharp-edged, etc…, just like you’d expect a piece of broken tooth to be). However, if the aspect you’re looking at is the tooth’s original outer surface, that side will have contours that are smooth and rounded (see picture for an example).

Those portions covered with dental enamel will be white and have a shiny appearance when dry. Aspects involving the inner portions of the tooth or its roots (both composed of dental dentin) will have a more yellowish tint, and a dull appearance when dry.

The size of the fragment can be quite variable. And like an iceberg, what you see sticking through your gums may in no way correlate with the full extent of what lies underneath (be it large or small).

Why do these bits and slivers come to the surface?

You may consider discovering a bone spur or piece of tooth poking through the gum tissue of your extraction site to be somewhat disturbing. But experiencing this phenomenon is actually a fairly common occurrence, and it’s easy enough to understand why it needs to take place.

Why it occurs.

- From your body’s perspective, these pieces of tooth and lumps of dead bone (sequestra) are foreign objects.

(They aren’t healthy, live tissue that can once again be a part of your body. To the opposite, their presence complicates and delays your wound’s healing process.)

- Since these objects have no beneficial value, and in fact are instead a complication, your body’s goal is to eject them.

What takes place.

Fragment migration.

The path of least resistance for these pieces is through the newly forming tissues of the healing socket. Then, once they’ve migrated to the surface of your jawbone, they begin to penetrate into the gum tissue that lies over it, until they ultimately wind up poking through and sticking out of its surface.

Shard discovery.

In cases where the object is somewhat rounded and relatively smooth, and especially if there’s a substantial portion of it still not sticking through yet, these pieces may feel like a small (possibly movable) lump in your gum tissue.

If instead the fragment has any degree of roughness or sharpness, it won’t take long for it to cut through. And it won’t take long for your tongue to find it, and probably be quite annoyed by its presence.

Exfoliation or removal.

If given enough time, most small fragments can be considered self-limiting, in the sense that they will ultimately work their way on through the gum tissue and at some point finally fall out (exfoliate) on their own.

For most of us, however, their presence is too much of a novelty or irritation, or the process simply too drawn out, and going ahead and removing the item (discussed below) is desired.

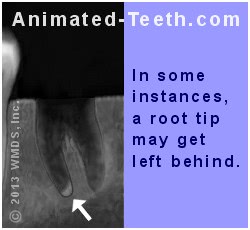

If this root fragment is not removed at the time of surgery it may eventually come to the surface on its own.

Post-extraction fragment timing.

When do the pieces first start to appear?

Some bits may take longer.

Some tooth fragments, especially root tips, may prove to be an exception to the above general rule. These shards may not surface for months (or even years later, if at all) after your surgery.

Risk factors / Prevention.

The likelihood of experiencing tooth and/or bone chips after an extraction is most likely to occur after those where the surgery involved has been relatively difficult or traumatic in nature. The paragraphs below explain why.

[And no, despite their best efforts no dentist can prevent them from occurring 100% of the time.]

a) Bone fragments (sequestra).

Bone is a living tissue and if it has been traumatized enough during the extraction process portions of this damaged bone may die. (When a sequestrum comes out, the piece you are looking at is literally a chunk of dead bone.)

What your dentist can do.

Your dentist’s overall goal will be to minimize the level of trauma that’s created during your extraction procedure. With this in mind:

- They’ll take great care whenever working directly with bone tissue, like during those times when the gums lying over it have been flapped back The procedure. so they have direct access to it.

This includes completing your procedure as quickly as possible and keeping the exposed bone moist.

- If trimming bone tissue with a drill, they’ll constantly flush it with water so it doesn’t become overheated by the process.

- They’ll limit the degree to which they continue to wrestle the tooth back and forth during the extraction process. That’s because the continued use of heavy forces may damage the bone surrounding the tooth, thus leading to its demise and ultimately sequestrum formation.

A paper by Early suggests that excessive deformation of the bone and/or bone trauma created by the use of rotational movements of the tooth during the extraction process are actions that tend to contribute to sequestrum formation. And in cases predisposed to the use of these techniques, that performing the extraction as a surgical one probably makes the better choice because it will likely result in less bone trauma.

b) Broken bone.

The bone that makes up a tooth’s socket is fragile, and aspects of it may break during the extraction process. If this occurs, a major issue is whether or not the blood supply to the fragment has been compromised or not.

If it is still intact, the fractured piece may heal. If not, it will become necrotic (die), and ultimately be ejected as a sequestrum.

Your dentist will thoroughly flush out your tooth’s socket to remove any loose debris.

Complete breaks.

- Any pieces that have broken free entirely and are noticed by the dentist can be picked out or washed away when the tooth’s empty socket is “irrigated” (flushed out with water or saline solution).

- Some bits may go unnoticed but will get flushed away anyway during the socket’s post-extraction irrigation.

Any fragments that have broken free that aren’t removed from the socket will ultimately be ejected as bone sequestra during the healing process and following.

Attached bone fragments.

Those broken pieces of bone that are still attached to tissue (still have a relationship with surrounding bone and/or gum tissue) and still maintain an adequate blood supply (the broken bit’s source of nourishment), may ultimately heal and therefore may be left in place by your dentist (this is a judgment call on their part).

If they don’t survive, they will become bone sequestra.

c) Tooth pieces.

Routine fragments.

Anytime a tooth does splinter or break, a dentist will make sure to thoroughly irrigate (wash out) the tooth’s socket with water or saline solution in an attempt to flush away any and all remaining loose bits.

Broken root tips.

While never a first choice, a dentist may decide that leaving a broken root tip leaves the patient at less risk for harm than the damage that might be caused by going ahead and trying to remove it.

A broken root tip left after an extraction.

- If the root remnant is 4mm or less in size (about 1/8th inch) and lies in close proximity to a vital structure (such as a nerve bundle, thin sinus floor, etc…), the risk vs. reward associated with removing the fragment (we describe possible complications below), as compared to just leaving it alone, must be weighed.

- Unless infected (a judgment based on the reason for the tooth’s extraction), leaving behind a small root fragment is usually of no consequence.

- Any pieces of broken tooth root that are left after an extraction should be periodically monitored via X-ray examination.

- Over time, there is a chance that the broken piece may migrate to the surface of the bone where it can be removed, possibly quite easily.

▲ Section references – Koerner

Risk vs. reward considerations associated with removing a broken root tip during a tooth’s extraction procedure.

As you can probably imagine, a small piece of broken root tip may be hard to visualize and access. And if so, the piece may be challenging to remove. (Usually, attempts at removal will involve the use of some type of dental elevator.)

In their zeal to remove a root tip, a dentist may inadvertently direct a greater level of force to the bit than the surrounding tissues can bear. As examples –

Potential complications with broken root tip removal.

- A root tip encased in thin sinus floor bone may break through and be inadvertently pushed into the patient’s sinus. A separate procedure will then be needed to remove the displaced piece. (This type of complication would be most associated with removing upper molars.)

- Excessive forces directed to the root tip could cause damage to nearby vulnerable nerve fibers, resulting in a complication termed paresthesia. (This type of complication would be most associated with lower molar extractions, especially impacted wisdom teeth.)

While these types of events aren’t necessarily common, they can occur. And in situations where the potential for experiencing a complication seems relatively possible, leaving the broken fragment alone in the first place may make the most prudent choice.

d) Your part.

There’s really not much you the patient can do to prevent extraction fragments other than giving your dentist your full cooperation so they can complete your procedure under as ideal circumstances as possible. (In more straightforward terms, make it so your dentist is able to focus more so on the process of performing your extraction, instead of managing you.)

Removing bone fragments and tooth pieces.

a) Treatment performed by your dentist.

It’s your dentist’s obligation to provide the assistance you require during your extraction site’s healing process.

So, if you’ve found anything hard or sharp sticking out of your gums at any time after your extraction (either initially or even some weeks out), you should never be hesitant to ask for their attention and aid.

What your dentist needs to do.

In short, your dentist simply needs to remove the shard. With the small types of fragments that are the focus of this page, the procedure is usually quite easy. However, and as explained below, larger bits may offer your dentist more of a challenge and require a more involved procedure.

How they’ll do it.

- With most cases, removing the offending piece usually just takes a quick flick or tug using a dental instrument or a pair of tweezers, with no anesthetic required.

- In some cases, the spur or sliver might be large enough and/or still buried under your gums enough that a longer, harder tug or push is required. If so, the use of some type of anesthetic might be in order.

Anesthetic options.

A dentist has two types of numbing agents that might be used:

- Topical anesthetic (i.e. benzocaine) – This type of product is usually a gel that’s smeared on the patient’s gums around the protruding fragment.

Generally speaking, a topical anesthetic is only able to numb up the surface of the gum tissue. But since that’s where the bulk of the fragment likely (hopefully) resides, its effects are usually sufficient.

- Local anesthetic (i.e. “Novocain”) – This type of anesthetic is given via injection (a dental “shot”).

This method of anesthesia provides a deeper, more profound level of numbing. The trade-off is that you’re likely to feel the pinch of the shot Why some shots hurt. as it’s given.

You’ll simply have to rely on your dentist’s judgment as to which method is needed for your procedure. They’ll base their decision on their interpretation of how small the object is and how quickly they expect it to flick out. Your concerns can be an important part of this calculation too, so let them be known.

Situations involving relatively larger fragments.

In some cases, your dentist may determine that the shard is relatively immobile. This might be because a substantial portion of it is still buried below the surface of the gum tissue. Or in the case of a sequestrum, it has yet to fully separate from associated bone tissue.

If this is the case, an alternative plan will need to be formulated.

a) Allowing the fragment more time.

Since your body’s goal is to completely eject the surfacing shard, allowing this process more time may provide a simple solution.

A plan might be formulated where the piece is checked by your dentist periodically (every few days to a week). And at that point when its removal seems possible, they will.

b) Surgically removing the fragment.

It may be decided that going ahead and removing the offending piece via a minor surgical procedure makes the better plan. To do so:

- After administering a local anesthetic, your dentist will make an incision in your gums along what they interpret is the object’s longer axis.

(A clean incision will heal more quickly than tissues that have been ripped or torn during the removal process.)

- Now that your dentist has adequate access to the piece, they’ll go ahead and hopefully tease it out easily and quickly. (But even your dentist won’t know exactly how much of a wrestling match it will be until they’re finished.)

- Once removed and depending on the extent of the incision made, placing a stitch or two may or may not be required.

▲ Section references – Farah, Wray

Taking an X-ray.

Your dentist may feel it’s necessary to evaluate your tooth’s socket by way of taking a radiograph.

- Since live and dying bone (sequestra) will both have a similar level of mineral content and therefore similar density, early on it may be difficult, if not impossible, for your dentist to precisely distinguish one from the other on an X-ray.

- In more chronic situations, differentiating between the two can be expected to be easier. Although with very small shards, probably still a challenge.

As tip-offs to your dentist: Your body may encapsulate the fragment in tissue, thus giving it a distinct appearance. Or because it has begun its migration, the bony piece may appear as an object out of place.

- Since tooth shards, root tips, and pieces of filling material each have a different density (and density pattern) than bone, they are much more likely to be visible on a radiograph.

Proactive treatment.

For small, routine shards, a dentist will usually just provide treatment for their patient on an as-needed basis (as each bit surfaces and is discovered sticking out of the gum tissue).

Less common is the scenario where the dentist goes after the pieces surgically before they surface. Here are some reasons why:

- As we’ve just explained, some types of fragments can be hard to identify on dental X-rays. And even if seen, routine X-ray imaging only provides a two-dimensional representation, which means that it can still be difficult to know exactly where the offending shard(s) lies.

- Visibility in an extraction site can be limited. Bleeding can further complicate this issue. Overall, especially when smaller, multiple fragments are involved, locating all of the offending bits may not be simple or entirely successful.

- Probably the biggest question is simply, why create a whole new surgical wound just to remedy a situation that your body will most likely handle relatively uneventfully on its own?

Having stated the above, when the fragments are relatively fewer and larger, or it’s your dentist’s interpretation that a piece will not shed so easily or uneventfully, the case for surgical intervention can make a lot of sense.

DIY – How to remove a small, hard object from an extraction site on your own.

- Wait until the object has partially penetrated the gums.

- As a test, wiggle on the bit. Look for at least some mobility.

- To remove, apply firm pressure to the fragment using your fingernail, tweezers, etc…

- Cycle through repeated applications of pressure (back-and-forth, up-down), looking for increased mobility each time that you do.

- Once the fragment is out, control any bleeding. (Like by biting on gauze.)

- If any questions exist, let your dentist investigate and complete the job. (The piece may be bigger or more firmly fixed than anticipated.)

- Refer to our text for more complete instructions.

b) Do-it-yourself / At-home treatment.

How to remove a bone fragment or piece of tooth from your gums at home.

You may be able to remove very small tooth and bone splinters that have worked their way to the surface of your extraction site (are poking through you gums) on your own at home.

- These bits can usually be flicked out using your fingernail, pulled out with tweezers, or pushed out by your tongue.

- It may take working the bit repeatedly over the course of a day or two until it finally gets to a point where it’s loose enough to come free.

- When it finally comes out, you’ll probably get a little bit of bleeding but it should be very minor. (Bleeding is best controlled by biting firmly on gauze. What to do.)

- If a portion of the shard hasn’t yet penetrated through your gum tissue (so you can get at it and manipulate it), you’ll simply have to wait until it has.

The only other option would be to request your dentist to remove it surgically (described above). After evaluating your situation, they can then determine if that option seems reasonable at this point or if instead the fragment should be allowed more time to work its way through the tissue before it’s challenged.

Anesthetic – possible options.

If you’re squeamish about the way things feel while wrestling one of these fragments out, you might consider:

- Using an over-the-counter gum-numbing agent. – Look for products (liquids, pastes, or gels) that contain the anesthetic benzocaine (ask your pharmacist). These are the same types of numbing agents that are often used with children to control teething pain.

- Applying ice. – Short applications of cold can produce a temporary numbing effect that may be enough to help. (Try rubbing a pointed piece of ice gently around the area.)

FYI – These types of numbing agents can only be expected to create an effect at the surface of the gum tissue, not deep inside, and definitely not at bone level.

So, for small shards that occupy a position just under the gums’ surface, (likely evidenced by being fairly mobile), these suggestions may help. But for larger, more involved fragments, it will probably take treatment from your dentist to keep you totally comfortable.

Best practices for at-home treatment.

Do-it-yourself treatment is fine for emergencies and when the bit comes out easily. But overall it just makes good sense to touch base with your dentist when any fragments show up. (It’s your dentist’s obligation to provide you with the post-extraction follow-up care you require.)

Here’s why …

If you’re generally a healthy person, and the area where the fragment has appeared was involved with a challenging extraction (which can be an explanation for its presence), then what’s discussed on this page likely applies to your situation. But for others, the event may be an indication of more serious issues.

As examples, people who have a history of taking bisphosphonate medications (like Fossmax®) or those who have had head and neck radiation treatments are at risk for serious complications with bone tissue healing. And therefore, the apparently minor shard they notice may instead be an indication of a more serious underlying condition.

Healing following fragment removal.

Since the wound that remains after removing a small fragment will primarily lie within the thickness of your gum tissue, once it’s gone you can expect healing and pain reduction to progress rapidly, with complete healing occurring within 7 to 10 days.

The actual time frame you experience will, of course, be influenced by the initial size (diameter) and depth of the wound that was left behind.

Steps you can take.

If tenderness in the area where the bit has been removed is a concern, the use of an over-the-counter pain reliever (like ibuprofen, aspirin, or acetaminophen) typically provides satisfactory relief. The use of gentle warm-saltwater rinses, three or four times a day, will promote faster healing.

Larger, more involved fragments.

As stated initially, the contents of this page apply to small isolated pieces of tooth or bone tissue that have suddenly appeared through the gum tissue surface of an extraction site following an otherwise uneventful healing process. Toward identifying cases that lie beyond the routine, we have a page that outlines the expected healing timeline for extractions. What’s normal?

If what you have experienced varies from the norm, you need to be in touch with your dentist for evaluation. Assisting you with any and all post-extraction complications is their obligation to you.

- Beyond the routine causes we describe on this page, some post-extraction fragments (bone sequestra especially) form for other reasons (pre-extraction bone infection, history of taking bisphosphonate drugs, history of radiation treatment involving the jaws, …), and therefore require more involved treatment.

- When larger and/or multiple fragments or chronic symptoms are involved, a dentist’s evaluation will be needed to determine how the patient’s case is best treated. Close monitoring, medication, and/or surgical intervention may be indicated.

Bone fragments not associated with a tooth extraction.

The contents of this page address the subject of small, routine bone spurs that rise to the surface of a patient’s gum tissue after a tooth extraction. Possibly producing a similar experience is the condition referred to as “uncomplicated spontaneous sequestrum.”

Just as above, the word “sequestrum” as used here (the plural form is sequestra) refers to dead, ejected bits of jawbone. However, with this condition, the cause of the sequestra is unrelated to the removal of a tooth. And in fact, the precise cause of the bone tissue’s devitalization (death) frequently remains unexplained.

A common location for the formation of these bone bits is the tongue side of the lower jaw in the area of the molars.

Why they form.

The usual explanation given for the formation of these sequestra is local tissue trauma.

- The idea is that the gum tissue in the affected region has been traumatized to the point where there is a disruption to its blood supply. This might take the form of continuous low-grade trauma, or a more substantial event.

- Due to the blood supply loss, the soft tissues that lie over the bone are less capable of protecting it, and as a result, it necroses (dies), ultimately resulting in the formation of a sequestrum (the body’s ejection of dead bone tissue).

Some suggested causes of continuous, low-grade trauma include abrasion associated with eating foods (in cases where there’s a less than ideal teeth-jawbone relationship or jaw shape, or an area of missing teeth) or trauma caused by repeated activities such as tooth brushing.

Treatment and concerns.

After evaluation, with very minor cases a dentist might conclude that the event has been a self-limiting condition that lies within the normal limits of what a person may experience.

With these minor cases, once the sequestrum has been lost (either spontaneously or assisted) the patient’s pain relief and healing will progress rapidly, with complete healing occurring within 7 to 10 days.

▲ Section references – Farah

Back to our post-extraction complications page. ►

Page references sources:

Ahel V, et al. Forces that fracture teeth during extraction with mandibular premolar and maxillary incisor forceps.

Early TE. Complications With Extractions.

Farah CS, et al. Oral ulceration with bone sequestration.

Koerner KR. Manual of Minor Oral Surgery for the General Dentist. (Chapter: Surgical Extractions.)

Sigron GR, et al. The most common complications after wisdom-tooth removal: part 1: a retrospective study of 1,199 cases in the mandible.

Wray D, et al. Textbook of General and Oral Surgery. (Chapter: Complications of extractions.)

All reference sources for topic Tooth Extractions.

Video transcription.

Hello, welcome to Animated Teeth.com and our page that discusses the issue of small bits of tooth or bone that sometimes come from a tooth extraction site. This may occur days, weeks, or possibly even months after the procedure was performed.

Using this video, we’ll point out some of the more important issues covered on this page that you should be aware of.

For starters, you may wonder where these fragments come from. Most of them are either bits of broken tooth or pieces of dead bone tissue. Your dentist calls bone fragments like these a sequestrum.

When a tooth is extracted, it’s not terribly uncommon for it to break. Teeth that are cracked, or are severely decayed or have large fillings, or those that have had root canal treatment may be structurally weak and therefore more prone to doing so. And despite the dentist’s best efforts in removing these bits, it’s possible that some pieces may get left behind in the socket.

In the case of broken root tips, the piece may still be bound in place. And if not noticed, it will stay behind even after flushing out the wound.

Actually, to get an idea if that might be an issue, a dentist will purposely feel the root of the extracted tooth. The surface of roots is generally rounded and smooth. So if the dentist discovers a sharp edge, they need to consider that part of the root has fractured off.

As far as bits of bone go, they may be broken pieces that have been left behind. More likely however, they’re a bit of traumatized bone tissue that has died and subsequently is being ejected by the body.

There’s a general relationship between the level of trauma that the surrounding bone tissue experiences during the extraction process and the potential for bone fragments later on. So, extractions that involve a lot of wrestling to get the tooth out, or an extended procedure time, or if the bone tissue must be directly manipulated, like trimming a portion of it away to get at the tooth, the patient is generally more at risk for experiencing a sequestrum later on.

As an interesting point, when examining the fragment that’s come out, it’s usually easy enough to determine what it is, bone or tooth.

If the bit has one smooth, slightly contoured side, it’s probably a shard of tooth. If it’s rough and irregular in shape overall, it’s probably necrotic bone tissue.

As far as the removal of extraction site fragments goes, the lower portion of our page outlines how dentists remove them. In regard to the possibility of using a do-it-yourself approach, it’s just going to boil down to the issue of if yours is small enough that you can.

The best plan is going ahead and contacting your dentist’s office and discussing your situation with them.

To your dentist, a complication like this is routine and not especially unexpected. They also know that in most cases, teasing the shard out is quick and easy. So, don’t be surprised if they just have you stop on by.

After discussing things with them, you may still decide, or even be instructed, to experiment a little on your own first. Keep in mind that a sequestrum or tooth fragment can be similar to an iceberg, in the sense that what you see or feel is only a portion of the whole thing.

Using your tongue, fingernail, or tweezers, you can experiment with applying pressure to the piece and judging how much it gives.

With small bits, applying pressure, possibly rocking the shard back and forth firmly, may very well loosen it up. In some cases, it may take some hours of periodic gentle persuasion to get the fragment out. With other cases, your efforts may be a few days too early because your body hasn’t brought the fragment close enough to the surface yet.

Besides more experience, better visibility, and better tools to use, yet another treatment advantage that your dentist can offer is that they can numb up your gums if that’s needed to get the piece out.

However, with a do-it-yourself approach you do have some numbing options too. Ice application can numb the top layer of your gums. As can over-the-counter anesthetic products, like those that contain benzocaine.

As a bit of advice, if your fragment doesn’t come out easily, promptly and uneventfully, let your dentist evaluate it and remove it. Your extraction was their work. They’re obligated, and probably very eager, to help you with any post-extraction complications that occur. You should take advantage of that.

Comments.

This section contains comments submitted in previous years. Many have been edited so to limit their scope to subjects discussed on this page.

Comment –

Nasty bone shards.

I didn’t see any reference to how excruciating these pesky shards are. I’ve had several, not due to an extraction, and they are no fun! They also don’t mention that your gun will not heal until the shard is removed.

Bev

Comment –

Bone fragments.

I had a tooth extracted mid January. Over the past several weeks the site has been sore due to what I believe are teeth or bone fragments working their way up through the gum. So far I’ve managed to extract only 2 teeny tiny pieces (which still blows me away because my tongue was telling me these were huge pieces of tooth or bone). My mouth is so sore all the time now. Should I wait until these fragments work their way out or go to my dentist to have them removed? I don’t want to go back to the oral surgeon who pulled my tooth. Can my regular dentist do it? Thanks for advice in advance.

Dj

Reply –

If you’re uncomfortable all of the time, it makes sense to check in with a dentist so they can pass judgment on what you are experiencing. Small, routine fragments are expected to be a non-issue until that point in time when they come through the surface of your gums and your tongue finally discovers them.

In regard to a proactive solution, fragments can be difficult to identify and locate (the smaller the harder), and for that reason a dentist may be hesitant to perform a surgical procedure to (hopefully) remedy what your body would have taken care of on its own. (For example, with multiple small bits it would be easy for some to be overlooked or not found and therefore left behind.) It just all depends on what they determine when they evaluate you.

The obvious choice of practitioners for your evaluation would be the oral surgeon since they performed your work, know your case, might consider this follow-up treatment as opposed to a separate procedure, and should generally have more experience with this complication than a general dentist.

But yes, a general dentist is perfectly capable of making an evaluation (and making a referral if needed) and/or removing extraction fragments, especially smaller ones already near the gum’s surface.

Hope this experience is over for you soon.

Staff Dentist

Comment –

Bone fragment.

Had my last 9 teeth extracted 5 weeks ago. Everything went well, except for 2 molars side by side on the bottom right. I was told by a previous dentist, he wouldn’t pull the 2 molars, that from the X-rays it showed they were really deep, and he suggested an oral surgeon.

I went for months, until I finally HAD to get them pulled, and got in to see a dentist I use to go to years prior. He said no problem, and pulled them. Literally took him max, 15 minutes to pull ALL 9 teeth! I thought it a little odd because he did it so quickly, and thought about the dentist who wouldn’t pull them because they were so deep…this guy pulled and tugged pretty hard, fragments went flying everywhere! I was gagging on broken chunks of teeth floating down my throat! Stitched me up, and sent me on my way…

The first week and the stitches started dissolving, one to the particular molar come loose, and the opening gapped open! Its been real slow healing in that one only, and I believe it’s the same molar that this razor sharp piece of bone is protruding through the gum, on the inside next to my tongue! Each movement from my tongue, feels like it is being sawed on! Hurts like all heck!

I have been back in to see this dentist 2 more times. They X-rayed it, and her said it is bone, and that in time it will work its way out. He said to leave it alone and don’t touch or mess with it. I went for another week, the pain was miserable! This time he decided to shave some of it off, it was very little, but it seemed to help for the time. It started to feel a bit better in a week, but now, it’s like it grew back or something! This is really getting to me, and most miserable!!! I don’t want to have to call him again, because he’s giving me the idea he has done all that he can for me. HELP PLEASE! I can’t live with this like this!

Lona

Reply –

We’ve taken some of the lines out of what you report and have added our comments, some for your benefit, and then others for the benefit of others reading about your experience.

You state the first dentist recommended having the teeth removed by an oral surgeon (“… and he suggested an oral surgeon …”). You don’t state whether the dentist that actually did the work was an oral surgeon or not (“… a dentist I use to go to years prior …”).

Both general dentists and oral surgeons can be expert at removing teeth. However, and as this page explains, the formation of bone sequestra is frequently related to the level of trauma created during the extraction process (… pulled and tugged pretty hard, fragments went flying everywhere! …”).

Either type of provider may encounter the exact same procedural difficulties and same outcome. But especially with difficult cases, the expectation would be that the added experience and advanced skills that an oral surgeon typically has would result in the creation of less trauma during the extraction process.

—

“… I have been back in to see this dentist 2 more times …” “… They X-rayed it, and her said it is bone, and that in time it will work its way out. He said to leave it alone and don’t touch or mess with it…”.

As we describe above, identifying the full scope of a bone sequestrum can be difficult. Over time the object can be expected to ultimately work it’s way out. That doesn’t mean however that at some point in time a dentist might not feel that conditions are right to speed things along by surgically removing the bit. Your dentist won’t be able to decide if this is an option unless you allow them to continue to monitor your situation.

“… but now, it’s like it grew back or something …”. This could be evidence that the bony bit continues to migrate up and out, which is what is supposed to be happening.

“… I don’t want to have to call him again, because he’s giving me the idea he has done all that he can for me …”. It is your dentist’s obligation to provide you with the post-operative care that you require.

All dentists understand that some cases will be simple and others won’t be. And while it may be that your solution only can be solved by allowing time and the bone fragment to pass, as mentioned, there may be a point where their assistance might provide a quicker outcome. And for that reason, they should encourage you to allow them to continue to monitor your situation.

If a different dentist will be providing denture services for you, you might go ahead and appoint with them for evaluation. They can double check that everything you are experiencing seems within normal limits, and that all of the proper ground work about your jawbone (general shape, contours, etc…) are appropriate for future denture construction.

Good luck with this. We hope your situation resolves soon.

Staff Dentist

Comment –

1 cm bone left.

I had my 4 wisdom teeth taken out last fall and became very sick. I was in constant pain. The oral surgeon kept telling me it was normal and I should not worry. It was the worst pain ever. I was going back to them several times a week for over a month because I could not deal with the pain and swelling.

6 weeks later they actually took time to examine the area and discovered a 1 cm bone chip in one of my sockets. Although they removed the bone chip I was very sick and wound up spending over a week in the hospital for infection. It was very expensive and made me sick for a long time.

Is this size bone chip normal or should I contact a lawyer to try to get money for all my hospital bills?

Mike

Reply –

What you describe really lies beyond the scope of this page and any information we have to share, but it seems reasonable to state the following.

You mention “wisdom teeth taken out,” so we’re assuming they were impacted teeth requiring surgical removal. Surgical extractions by nature are traumatic events for bone tissue, thus increasing the likelihood of post-extraction sequestrum formation.

You mention an “oral surgeon” performed the treatment. General dentists sometimes get involved in performing extractions beyond their skill level, one wouldn’t think that applies in your case.

As far as the incidence rate of sequestra formation, we found a study by Sigron (2014) (see page reference sources link above) that followed over 1000 lower wisdom tooth extraction cases and determined that the incidence rate for sequestra was 0.3%. (An associated study involving upper wisdom teeth didn’t even mention this complication.) Despite that seemingly low number (the highest incidence rate reported for a specific complication by this study was 4.2%), sequestra formation is certainly a known complication.

As far as size, our unqualified opinion would be that 1 cm cube would lie in the “not small but certainly not unheard of” range.

We should also mention that your comment is titled “1 cm bone left.” As this page describes, the more likely scenario is that the bone tissue at the time of the extraction was stressed beyond repair, and was ultimately ejected by your body because it finally died, but the word “left,” as in left behind, probably is not an accurate description.

We would think that the management of your case was more of an issue than the event itself (“6 weeks later they actually took time to examine …”).

Just when your complication could have/should have been anticipated/suspected/identified/treated lies beyond our level of expertise. We’re glad you’re OK now but really have no qualified opinion to offer about what transpired.

Staff Dentist

Comment –

Bone spurs after tooth extractions.

I had my teeth extracted over four months ago and I’m having problems with bone pieces under my gums that are getting more annoying and painful. I haven’t got dentures yet because of the fear these bones will interfere with the process of forming my new dentures and fitting properly afterward.

Roger B.

Reply –

You need to go ahead and appoint with the dentist who will ultimately make your dentures. It’s common and routine to be evaluated by them first in preparation of your returning for denture construction (even if it is months later). During their exam they can evaluate what you are experiencing and make plans from there.

It could be that what you notice is fragments. If that can be determined, possibly a simple surgical procedure (like that described above) could be used to remove them now, so complete healing can go ahead and occur and you can be more comfortable.

Or it could be possible that what you feel isn’t loose fragments but instead the irregular sharp/pointed surface of the bone. If so, the bone may need to be rounded off (alveoloplasty) before successful denture construction can be accomplished.

Either way, you need evaluation.

Staff Dentist

Comment –

Had 6 teeth were pulled and denture made.

This was done over a month ago. Had bone spur And dentist smooth it, now about 2 weeks later it is back, I have not been able to ware the denture for bone spurs and sores. What is the best next move to solve this problem?

LH

Reply –

Your solution still lies with your dentist. Having them evaluate your current situation and recommending a solution.

You state “Had 6 teeth were pulled and denture made … This was done over a month ago.”

What you don’t say is if your case involved an “immediate denture” or not (your teeth extracted and the denture placed on the same day).

Generally speaking, the healing process for bone tissue takes months. During this time period the shape of the bone changes (transforms from the irregular post-extraction status to a more filled in and smooth shape).

In the case of an immediate, you’re simply wrestling with multiple issues (denture fit, learning how to wear dentures and bone healing) all during the same time frame. And your dentist fully expects this type of case to require added assistance and attention while the healing process takes place. So be back in touch with them. (You use the term “spurs.” We’re not sure whether this means irregular ridge contours or actual fragments coming out, both tend to resolve over time but you probably need assistance with them.)

As a side note, in some cases a dentist might determine that the use of a soft denture liner (likely a temporary one) might be of aid in helping you through this troublesome period when maintaining denture comfort is an issue.

Staff Dentist

Comment –

Piece from tooth #3 left in.

I had an extraction of number 3 and number 4 about 6 hours ago and now I can feel a small piece still in there what should I do? Small meaning it feels like a piece of 3 grains of rice stuck together

Barbara W.

Reply –

During the first 24 hours your job as a patient is to leave your extraction site alone, so blood clot formation and retention are not disrupted.

As for treatment, you need evaluation by your dentist so they can determine what it is you feel.

If it is a loose shard of tooth or bone, they will remove it.

If the piece is immovable, with larger extraction sites (molars/multiple adjacent teeth, you mention both), objects in the area your tongue can feel may be exposed bone.

If so, your dentist may smooth it off, or at least explain to you what you feel.

As far as immovable remnants of your teeth. Those objects would be expected to be so deep in the socket that it would be unlikely that you could feel them.

Whatever your problem, contact your dentist’s office and have them evaluate you.

Staff Dentist

Comment –

T6 tooth removal.

I just removed my t6 tooth and while he was doing that, a fragment of one of the roots broke and couldn’t be found.

Please is there any side effects leaving this fragment. ?

Blessing

Reply –

Without knowing any specifics, what we state above about tooth fragments (root tips) is about all we can say.

It does seem that the dentist should make some attempt to identify where the root tip is. It would be important to know that it is in the socket, as opposed to having been displaced (like with upper molars into a sinus).

It’s usual that root tips are monitored periodically by taking an X-ray so to evaluate their current position and for signs of complications (like an infection).

Staff Dentist

Comment –

Bone bits.

This seems very useful for my mother. She had a tooth extracted but continues to have problems with bone fragments.

I have questioned her accuracy.

LCB

Reply –

If your mother hasn’t, she should still touch base with her dentist and relate to them what she has been experiencing so they can pass judgment on her situation.

While you don’t mention your mother’s age, as mentioned here on this page, a history (even at some point distantly previously) of taking some medications, like Fossmax® (a bisphosphonate medication often used to treat osteoporosis in elderly women), can interfere with normal bone healing. Those conditions need special attention.

Staff Dentist