Causes of failed root canal. – Reasons why endodontic therapy may fail. / Treatment solutions.

Root canal treatment failure.

Why it occurs. What can be done.

While generally a highly successful procedure, some root canal cases do fail. This guide explores the most common reasons for RCT failure, the associated symptoms, and available solutions.

Our guide covers the primary causes of failure, such as missed canals, cracked teeth, or inadequate internal or external seals. Additionally, it explains possible treatment solutions for each type of case failure, including conventional vs. surgical retreatment, or even tooth extraction when necessary.

By understanding the reasons for endodontic failure and possible treatment options, you can work closely with your dentist to determine the best path forward for your tooth and overall dental health.

FAQs: Quick details about failed root canals.

a) What is a failed root canal?

Well, with successful cases …

The goals of performing the tooth’s therapy have been met. The procedure has been successful in removing inflamed, infected, or necrotic pulp tissue from within its nerve space. And the treatment has been successful in sealing off this space so further infection is prevented.

With failed cases …

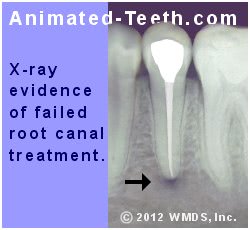

A situation exists where despite having received treatment, the tooth continues to display signs of persistent infection, inflammation, or other complications. (This may occur either initially or later on.) In essence, the treatment’s attempt to resolve the tooth’s issues has not been successful.

b) What happens when a root canal fails?

Generally speaking, endodontic failure is associated with either:

- Continued infection in the tooth’s nerve space. (The tooth’s treatment has been ineffectual in resolving its pathology.)

- Or a successfully treated tooth has become reinfected due to events that occurred later on. (Like tooth breakage, root cracking, or bacterial seepage.)

c) What are the symptoms of a failed root canal?

Common signs include:

- Tenderness in the tissues around your tooth. | Persistent pain (intermittent or steady discomfort, possibly throbbing). | Tissue swelling (around your tooth and possibly extending into your face).

- Your tooth may be sensitive to pressure (tapping or biting on it) and may exhibit thermal sensitivity (especially to hot foods and liquids).

- In some cases, a recurring abscess (a transient pimple-like swelling or boil) may form on your jaw near your tooth that may, at times, discharge pus (and a bad taste).

What should you do if you suspect that your tooth’s root canal therapy has failed?

If you’ve noticed any signs of root canal failure, you should consult with your dentist promptly so they can evaluate your situation and initiate an appropriate plan of action.

Infected teeth can be unpredictable and the consequences of experiencing an acute tooth flare up (pain/swelling) can be significant. Additionally, allowing chronic infection to persist may complicate your tooth’s retreatment or result in events that compromise its neighboring teeth.

Contacting your dentist promptly and following through with their recommendations in a timely fashion are important steps in helping you avoid complications.

d) Why do root canals fail?

A tooth’s endodontic therapy may fail for a host of reasons, however, they all tend to fall into one of the following three categories.

- Diagnostic or procedural issues and errors that might have been handled more successfully during your treatment.

- Factors related to the characteristics of your tooth, its root canal system, or its condition at the time of its treatment that made your case more challenging.

- Some type of event has occurred since your tooth’s treatment was completed that allowed bacteria/oral contaminates to reinfect your tooth.

Specific reasons for root canal failure.

This subject is the primary focus of this page and we cover the following causes of endodontic failure, in detail, below. (Use the links to jump ahead.)

- Overlooked/Missed root canals.

- Unfilled accessory or lateral canals.

- Cracked teeth/roots.

- Unfilled/Ineffectively filled root canal system.

- Overextension of filling materials (overfill).

- Inadequate coronal seal.

- Clinician procedural errors.

- Preoperative pathology.

- Lack of clinician expertise.

- Compromised tooth condition.

e) Can a failed root canal be fixed?

Yes, in many cases endodontic retreatment is possible. The procedure that’s needed may either be:

- Conventional retreatment – This method (also referred to as non-surgical retreatment) basically involves performing your original root canal procedure again.

- Surgical retreatment – With this approach (also referred to as apicoectomy or just endodontic surgery), the problematic portion of the tooth’s root (typically just a small portion of its root tip) is surgically accessed and trimmed off.

With some cases, both procedures may be needed. (As our page explains each “failure reason” (see list of links above), we also cover what retreatment solutions may be possible for that situation.)

What if you don’t opt for retreatment?

Unfortunately, with a failed root canal there is no middle ground. The tooth either needs to be retreated (so its problems are cleared up) or else the tooth needs to be taken out.

Why would extraction be required?

Extraction is indicated because allowing an infected tooth to remain untreated creates an unpredictable situation (the tooth might flare up at any time). Also, allowing chronic infection to persist may seriously compromise the tooth’s surrounding bone tissue, possibly affecting neighboring teeth.

You’ll have a lot of factors to consider.

Making a decision about what to do about a failed tooth is never easy. If you’re leaning toward retreatment, your dentist will need to explain how much treatment time and what costs will be involved. You’ll also need to quiz them about the expected long-term outlook for your tooth’s repair. (We discuss success rates below.)

Despite what you might expect, opting for tooth removal doesn’t necessarily make the simpler or cheaper choice. Ideally, you’ll have your missing tooth replaced, which leads to a multitude of additional decisions that must be made.

d) What is the failure rate of root canals?

Endodontic therapy has generally been demonstrated to have a high success rate. In our “How common is root canal therapy failure?” section below, we cite several studies that report three to eight-year success rates of 85% and higher.

In regard to case failure statistics:

- Certain types of “failure causes” tend to lie at fault more frequently than others. (When we’ve found specific statistics to share, our text includes this information.)

- Who performs your treatment (endodontist vs. general dentist) tends to come into play. (Not surprisingly, the work of specialists has a generally higher success rate.)

- Which type of tooth has been treated is a factor too. (Multi-rooted teeth like molars are more difficult to treat than single-rooted ones, like canines and incisors.)

- In regard to retreatment, success rates also vary per the method that’s used (conventional vs. surgical).

A) Reasons why RCT cases fail.

Root canal therapy failure occurs when some type of factor The list. has interfered with the successful completion of one or both of the fundamental goals of endodontic therapy, which are thoroughly cleaning and then sealing off your tooth’s root canal system.

So, when case failure occurs …

- Something about the cleaning aspect of the tooth’s procedure The steps. has been incomplete or ineffectual and the irritants that remain inside your tooth have caused its treatment’s failure.

- Or else, the endodontic seal created for your tooth (either during its root canal procedure The process. or by its final restoration placed afterward What kind is needed?) has not been successful in keeping contaminants from seeping into, or out of, your tooth.

The seal might have been deficient initially. Or was initially intact and has since deteriorated or become compromised.

What can be done for failed cases?

For each cause of endodontic failure we list below, we also explain how the tooth’s situation might be remedied. However, there are usually only two options available, case retreatment (either by conventional or surgical means) or tooth extraction. Why?

Specific reasons why root canal treatment may fail.

- Overlooked/Missed root canals.

- Unfilled accessory or lateral canals.

- Cracked teeth/roots.

- Unfilled/Ineffectively filled root canal system.

- Overextension of filling materials (overfill).

- Inadequate coronal seal.

- Clinician procedural errors.

- Preoperative pathology.

- Lack of clinician expertise.

- Compromised tooth condition.

1) Missed canals.

Different types of teeth (molars, premolars, canines, incisors) characteristically have differing numbers of roots and root canals. What’s normal? | Variations. But unfortunately for the treating dentist, there are no hard rules about the configuration that actually exists.

- Specific roots of some types of teeth are well known for having, or frequently having, multiple canal configurations, and because of this should always be suspected of having more than one.

- Even beyond what might generally be expected, it’s always possible, no matter how rare, that the anatomy of a tooth’s root canal system is simply atypical.

The back root (root “a”) of a lower molar may have one or two canals.

If it has two but both aren’t found, its root canal treatment will fail.

A dentist’s due diligence.

The problem/question that arises is how much effort a dentist should reasonably expend in searching for these, possibly rare, variations.

As a point of fact, additional canals are frequently tiny in size and can be very difficult to identify. Additionally, they may have a location inside the tooth that’s strange or unexpected.

- At a minimum, looking for possible variations takes additional time. Although, this should just be a minor consideration for the dentist.

- Worse, searching a tooth exhaustively can involve trimming away aspects of its interior that can result in weakening it structurally. Of course, this can be especially disappointing when no additional canals are discovered.

For these reasons, it’s easy enough to understand why a dentist might not be astoundingly inquisitive if the configuration they have already discovered lies within the parameters of what can be considered normal for the tooth involved.

The underlying problem.

The crux of this issue is simply that any untreated (overlooked, undiscovered) canals, no matter how minute in size, will remain untreated and therefore a locus of persistent infection. And as such, that leaves the expectation that they will lead to the failure of the tooth’s root canal treatment.

Incidence rates.

An endodontist using a surgical microscope.

- A study by Iqbal determined that missed canals are a major cause of root canal failure (around 18% of failed cases), and are most commonly associated with treatment provided by general dentists as opposed to specialists.

(It’s common for an endodontist to use a surgical microscope as a visual aid in their search for additional canals. Also, a specialist is more likely to be familiar with what variations might exist and more likely to be able to adequately treat very tiny, narrow canals. See discussion and link below.)

- A study by Hoen evaluated 337 failed root canal cases and determined that overlooked canals played a role in 42% of them.

▲ Section references – Iqbal, Hoen

What’s the treatment solution for failed cases involving missed canals?

If the untreated canal(s) can be identified and located, conventional retreatment of the case The procedure. is frequently successful. However, your dentist won’t be able to give you any guarantees. Otherwise, the tooth will need to be extracted.

Should you opt for retreatment?

It may depend on who is offering to do the work.

- If the person who provided your tooth’s initial work now seems surprisingly confident that they can locate and treat the missed canal, well…

- If a second dentist has made the diagnosis, that’s somewhat different. Maybe your initial work was flat-out sloppy and treating the missed canal should be a fairly straightforward matter.

- As another option for retreatment, you might consult with an endodontist (root canal specialist). It’s hard to imagine that any general dentist could make a persuasive argument that they could offer as much expertise in handling difficult cases as a specialist. And because overlooked canals are often very minute and therefore hard to locate, clean, shape, and fill, the expertise of a specialist is often warranted.

Should you opt for having your tooth removed?

If your dentist, or especially an endodontist, suggests that extracting your tooth makes the best plan, you should probably take their advice.

Short of that, there are so many decisions to be made (your wishes, costs, no treatment guarantees, tooth rebuilding, tooth replacement, treatment timing, etc…) that making a decision between your options is never an easy one to make.

FYI: The lower portion of this page discusses the issue of Endodontic retreatment vs. Tooth extraction Jump and we encourage you to read it. It won’t answer all of your questions but it should give you enough information that you can have an intelligent conversation with your dentist about your situation.

2) Unfilled accessory and lateral canals.

The anatomy (shape) of a tooth’s root canal system may feature variations. Two fairly common ones are the presence of lateral and accessory canals.

Variant root canal anatomies.

- An accessory canal is a canal that branches off one of the tooth’s main canals and has its own separate exit point on the root’s surface.

Somewhat arbitrarily, accessory canals are usually defined as canal branching located in the apical end (tip portion) of a tooth’s root (last 1/3 of the root or so).

- A lateral canal is technically an accessory canal. But, again arbitrarily, usually defined as branching found in the upper 2/3rds of a tooth’s root.

- As a point of difference, lateral canals often run horizontally from the central canal directly to the root’s surface. In comparison, accessory canals typically have a more split-off or branching configuration. (See animation.)

The underlying problem with accessory canals.

With both of the above variations, it’s common that the canal branch isn’t identified by the dentist (they frequently can’t be observed on dental X-rays). And even when detected, it may be difficult, or even impossible, for the dentist to adequately treat (clean, shape, fill) the branch.

If that’s the case, and just like with missed canals discussed above, the result will be one where some of the tooth’s root canal system is left untreated (or at least ineffectively treated). As a result, the deficient portion can provide a location where infection can persist and therefore act as a continued irritant to the tissues that surround the tooth’s root, ultimately leading to case failure.

Incidence.

The root canal system of any tooth has the potential to include accessory canals. (They form when tissues that play a role in root formation become entrapped during the calcification process.) And, in fact, their presence is quite commonplace.

An evaluation of 493 extracted teeth by Ricucci determined that 75% of them had accessory/lateral canals. The question then arises, if they are so common, and they are difficult to clean and fill, why aren’t they a dominant factor in root canal failure?

Studies suggest that the size of the accessory canal and the contents it harbors (like microorganisms and their associated byproducts) are key determinants in the outcome of the tooth’s treatment.

▲ Section references – Ricucci

What’s the solution for failed cases involving untreated lateral or accessory canals?

Once the untreated canal(s) has been identified, it may be possible to successfully retreat the tooth conventionally (repeat its original root canal treatment process).

An obstacle to performing this work can be the fact that accessory/lateral canals sometimes branch off from the tooth’s main canal at a sharp angle. The dental instruments used when performing root canal often can’t negotiate these kinds of tight turns, which makes it generally impossible to properly clean, shape, and seal them.

Another possible treatment solution is surgical retreatment Explained.. In short, this is a procedure where the problematic portion of the root (typically just a small portion of its root tip) is surgically accessed and trimmed off.

In situations where your dentist doesn’t feel that any reasonable retreatment options exist, they’ll have to recommend that your tooth should be extracted.

FYI: For more information about endodontic retreatment options and factors to consider when making a decision, use this link. Endodontic retreatment vs. Tooth extraction Jump.

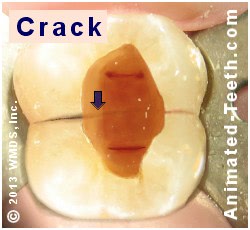

3) Cracked roots.

Cracks that form in a root canaled tooth’s root are vulnerable to bacterial colonization. However, unlike root canals that can be cleaned and sealed off (like during the tooth’s original treatment), there’s no way to treat the minute crevices that form as a result of tooth cracking.

Some fractured teeth may not be treatable.

That means that once a crack has formed and has been invaded by bacteria, the tooth’s status will ultimately fail. Short of amputating the affected root (if this option is possible at all), case retreatment (performing root canal treatment to clear up this new infection) is unlikely to provide a solution.

Difficulties.

There are several issues that can make dealing with cracks especially difficult:

- When performing a tooth’s endodontic therapy, a dentist may be unaware that a crack exists (they can be very difficult to identify), or they may underestimate the extent of the ones they see. Either way, the tooth’s problem (infection residing in these cracks) can’t be resolved by performing root canal treatment.

- It may be that the crack that caused the tooth’s failure formed after it received its endodontic treatment.

This scenario might occur if an inadequate “final” restoration was chosen for the tooth (one that didn’t provide enough strengthening effect). Or its permanent restoration was not placed soon enough (the damage occurred while the tooth’s temporary restoration was still in place).

- It’s also possible that what seemed to be a minor, manageable crack at the time of the tooth’s treatment instead progressed. (Especially if the chewing or clenching forces the tooth has been subjected to are intense enough.)

▲ Section references – Torabinejad

What’s the solution for failed cases involving fractured roots?

Your dentist may determine that removing your tooth is the only option that exists. That’s because they can’t condone a situation where there’s a perpetual infection associated with your tooth. And since this problem can’t be remedied, the only option left is to take the tooth out.

With multi-rooted teeth (primarily molars) it may be possible to salvage the problematic tooth by cutting off its fractured root (root amputation). Many factors must be evaluated before this solution can be proposed. (Will the tooth be structurally sound with less root structure? Is there adequate access for the procedure? Does the jawbone’s and tooth’s anatomy allow for this procedure.) Root amputation isn’t a viable option in all cases.

4) Inadequate root canal seal.

The integrity of the seal that’s created inside a tooth during its root canal procedure is an important factor in its treatment success.

- It acts as a barrier that prevents seepage of bacteria and other contaminants both into or out of your tooth.

(Microorganisms seeping into your tooth would reestablish infection in your tooth’s root canal system. Leakage of residual contaminants from inside your tooth would be a constant source of irritation to the tissues that surround its root.)

- The materials used to seal your tooth physically occupy the space of its root canal system. (Empty space may be a harbor for bacteria.)

(A study of 90 failed cases by Iqbal determined that 1/3rd involved underfilling the tooth’s root canal space.)

As an explanation of what has occurred that has led to your tooth’s treatment failure, it’s possible that the tooth’s once intact seal has deteriorated over time. Or it may have been deficient even initially (due to underfilling, the presence of voids, operator error in the way your tooth’s canals were shaped, etc…). Only your dentist can speculate.

▲ Section references – Iqbal

What’s the solution for cases that have failed because they’ve lost their endodontic seal?

Conventional retreatment (repeating your tooth’s root canal procedure again) is often successful with these kinds of cases and, per your dentist’s recommendation, usually makes a good choice. If your tooth isn’t going to be endodontically retreated in some manner, the only other option is to extract it.

Of course, a lot of factors (both pros and cons) must be weighed when making your decision. For more information about the options you may have and factors that should be considered, use this link. Endodontic retreatment vs. Tooth extraction Jump

5) Overextension of the tooth’s filling material.

Studies have shown that in cases where the materials used to fill in and seal a tooth’s root canal space extend out beyond its root’s tip (overfilling, overextension), the likelihood of endodontic failure is increased. (Tabassum)

- In an evaluation of 337 failed root canal cases, Hoen determined that overfills played a role in 3% of them.

- Iqbal’s evaluation of 90 failures found that overfilled canals played a role in 10% of cases.

The cause.

A primary problem involved with this issue is one of bioincompatibility. Due to the presence of the materials, a foreign body/inflammation response may be triggered in the tissues surrounding the root’s tip.

This response doesn’t occur in all cases. And in fact, it’s possible for normal and complete postoperative healing to occur in the presence of an overfill.

As a final point, while it’s true that in clinical practice unforeseen events sometimes occur, generally speaking, the ability to properly confine root canal filling materials within a tooth must be considered a factor that correlates with the clinician’s level of experience and skill. (See specialist vs. general dentist discussion below.)

▲ Section references – Tabassum, Iqbal, Hoen

What’s the solution for cases that have failed related to the overextension of root canal filling materials?

- Successful conventional retreatment of the case may be possible (repeating the tooth’s original root canal procedure).

- In situations where the overextended materials can’t be retrieved, surgical retreatment may be necessary. (A process where the tip of the tooth’s root is accessed surgically and the offending materials, and possibly the tooth’s tip itself, removed or trimmed.)

(It’s possible that your dentist may feel that conventional retreatment should be performed first and your surgical retreatment implemented as a second step.)

- If endodontic retreatment of some sort is not chosen, the tooth should be extracted.

For more information about the options you may have and factors that should be considered, use this link. Endodontic retreatment vs. Tooth extraction Jump

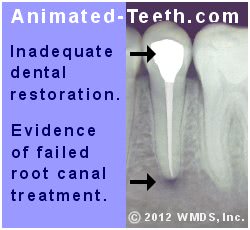

6) Inadequate coronal seal.

A defective or inadequate final restoration (the “permanent” one placed after the completion of a tooth’s endodontic treatment) may allow bacteria and other contaminants to seep past it and reenter the interior of its tooth.

The outcome of coronal leakage.

This phenomenon is referred to as “coronal leakage” and it is a major cause of root canal failure. We feel that this topic is important enough to give it its own page, so for more details use this link: What is Coronal Leakage? Causes. | Prevention.

Even the highest quality root canal work can’t survive (prevent reinfection of the tooth’s root canal space) if its tooth’s permanent restoration doesn’t provide an adequate seal. The study by Hoen cited above reported that 13% of failed cases involved complications with coronal leakage.

What’s the solution for cases that have failed because they have lost their coronal seal?

Conventional retreatment (repeating your tooth’s root canal procedure again) is frequently successful with these kinds of cases and, per your dentist’s recommendation, usually makes a good choice. Following that, a new “final” restoration will need to be placed. (That’s usually the best option following conventional retreatment anyway.)

If your tooth isn’t going to receive some type of endodontic retreatment, the only other option is to extract it.

Of course, a lot of factors (both pros and cons) must be weighed when making your decision. For more information about the options you may have and factors that should be considered, use this link. Endodontic retreatment vs. Tooth extraction Jump

7) Additional technical shortcomings that can cause root canal failure.

Beyond the clinician-associated issues mentioned above, other technical/procedural errors and complications can arise and have a detrimental effect on the treatment outcome of a tooth. This might include:

- Failure to treat the entire length of the tooth’s canals. – An important aspect of the root canal process is establishing the length of each of a tooth’s individual root canals How this is done., and then treating this entire distance.

Falling short can result in leaving debris and contaminants behind that can be a constant source of irritation to the tissues that surround the tooth’s root, thus resulting in treatment failure.

- Problems caused when shaping the canals – A dentist’s use of root canal files may inadvertently create an internal configuration that deviates from normal canal anatomy. (Applicable terms include: canal ledging, apical transportation, or zipping.)

This kind of alteration can make the process of cleaning and/or sealing the affected canal(s) difficult or impossible.

- Perforations – When using drills or files, a dentist may inadvertently create a hole Perforation. that penetrates the side of the tooth’s root.

Depending on the size and location of the perforation, some can be repaired successfully. However, in some instances the presence of the opening may make it difficult or impossible for the dentist to slide their tools and sealing materials beyond that point, thus inhibiting complete (proper) canal cleaning and sealing.

- Broken instruments – The files Details. | Pictures. that a dentist uses to clean a tooth’s root canal system sometimes break. It’s generally attributed to manufacturing defects, fatigue from usage, or with rotary instruments, creating a situation that places too much torque on the file.

As a worst-case scenario, the broken piece may be lodged inside the tooth and cannot be retrieved. If so, while leaving the fragment inside the tooth is never the dentist’s first choice, the point during the treatment process when the incident occurred may be a mitigating factor.

If the file separation has occurred after the canal’s cleaning process has already been completed, then possibly the canal can still be adequately sealed even with the fragment present. If the incident occurred during the cleaning process and inhibits its completion, the prognosis for the tooth’s treatment is much less favorable.

Statistics.

The study of 90 endodontic failures by Iqbal cited above determined that about 6% of the cases could be attributed to problems associated with perforations, and 7% broken instruments.

What’s the solution for these kinds of failed cases?

If your dentist feels that they can overcome or correct the difficulty associated with your case’s failure, then their performing conventional endodontic retreatment (performing your root canal treatment again) is indicated. If instead they feel that the tooth’s existing obstacles are too great, your tooth will need to be extracted.

Depending on the location of the treatment obstacle, in some cases surgical retreatment Explained. may offer a solution. In short, this is a procedure where the problematic portion of the tooth’s root (typically just a small portion of its root tip) is surgically accessed and trimmed off.

With difficult cases, it should be kept in mind that a root canal specialist Endodontist may have capabilities (skills, expertise, and equipment) beyond what a general dentist has to offer and therefore may be able to salvage a tooth that’s otherwise deemed hopeless. For this reason, you might ask your dentist if seeking the opinion of one is warranted.

For more details about options, see this page’s Endodontic Retreatment section. Jump

8) Lack of clinician expertise.

Research suggests that treatment performed by endodontists (root canal specialists) tends to have a higher success rate Study findings. than that provided by general dentists.

For example, the study by Iqbal cited above that evaluated failed cases determined that roughly 80% of them had been attempted by general dentists. (See additional statistics below.)

Why referral to a specialist may make sense.

Any dentist can tell you that providing endodontic therapy for some teeth can be amazingly straightforward, and then for others, surprisingly involved. Unfortunately, which level of difficulty will be encountered can’t always be predicted.

For this reason, some dentists may feel they can boost their patient’s chances of success by referring suspect cases on to an endodontist before complications arise. Per the data found in our failed root canal section Statistics., this might be an especially prudent choice for certain types of teeth (like molars).

Additionally, our page “Endodontist vs. General Dentists- Which makes the best choice, and when?” How to choose. discusses this issue in detail.

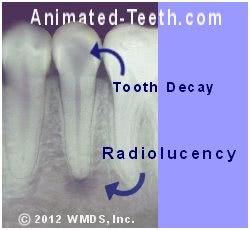

9) Preoperative tooth pathology.

A tooth’s initial status may play a role in the ultimate success or failure of its endodontic work. One such concern involves teeth that have a “periapical radiolucent lesion”.

A periapical radiolucent lesion.

Teeth having pre-op radiolucencies may be more likely to fail.

These types of lesions may continue to harbor bacteria despite the successful completion of the tooth’s root canal treatment. If so, this (external to the tooth) locus of infection will be a persistent irritant to the surrounding tissues.

The Iqbal study cited above suggests that the success rate of teeth having this initial condition (vs. those that don’t) may be lower, on the order of 20%.

What’s the solution for these types of failed cases?

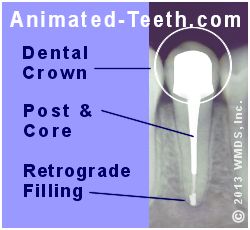

In cases where the dentist’s evaluation of the quality of the tooth’s previously performed root canal treatment seems acceptable, the solution for this situation may be a minor surgical procedure referred to as an “apicoectomy with retrograde filling.”

During this procedure, the tip of the tooth’s root is trimmed away. The exposed root canal opening on this trimmed surface is then sealed by placing a filling (a “retrograde” filling).

10) Contributing / Complicating factors.

It’s possible that your tooth’s root canal treatment has been successful but the tooth itself has problems due to other factors.

a) The tooth has broken or fractured.

Teeth that have had endodontic treatment are typically considered less structurally sound than they were originally, possibly substantially so. And for this reason, they often require the placement of a dental crown for strengthening and protection. How it does that.

If an endodontically treated tooth does break, it’s not always a big problem.

- Assuming that the damage is confined to just the crown portion of the tooth (not its root), it’s quite likely that the tooth can be rebuilt. (In some instances, the repair may require the placement of a dental post and core. When is this needed?)

- If the crack extends into the tooth’s root, an evaluation will need to be made to determine if the likelihood of making a successful repair seems possible (see above).

b) The tooth has extensive decay or gum disease.

Just like any other tooth, teeth that have had root canal treatment are at risk for the formation of tooth decay and gum disease. And if allowed to advance, either of these conditions can ultimately lead to the tooth’s loss.

What’s the solution for these types of failed cases?

If the tooth’s condition can be corrected or overcome, then conventional endodontic retreatment (repeating the tooth’s root canal procedure) is indicated. If not, then the tooth will need to be extracted.

B) How common is root canal therapy failure?

- RCT success rates. – Overall, all teeth considered.

- RCT success rates for general dentists vs. endodontists.

- RCT failure rates by tooth type.

1) Root canal treatment success rates.

For our reporting on this issue, we’ve chosen to cite statistics from three research studies that collectively have evaluated the outcomes of literally millions of treated teeth.

FYI: The usual source of data used for studies involving large populations is dental insurance company databases.

Chen (2007) –

This study evaluated the 5-year outcome of over 1.5 million teeth that had received conventional root canal treatment.

(We’re using the term “conventional” to refer to routine nonsurgical endodontic therapy The steps., which is the standard procedure you can expect your dentist to perform for your tooth.)

- 90% of the teeth were retained (still in the patient’s mouth and functioning) at a point 5 years after their original treatment. (This group of teeth had required no additional attention.)

- 3% of the studied teeth did experience root canal failure but were salvaged via performing some type of endodontic retreatment procedure. Possible options.

(By adding in this group of successfully retreated cases, 93% of all of the evaluated teeth were retained at a point 5 years out via the use of endodontic procedures.)

- The remaining 7% of teeth experienced failure and were extracted.

Raedel (2015) –

This study accessed a dental insurance database to determine the outcome of over 500,000 conventional root canal cases over their initial 3-year period.

Case failure was equated to the fact that following its treatment, the tooth was later documented in the database as either having non-surgical or surgical retreatment, or else it was extracted.

Using these parameters, the following survival rates were observed: 1 year – 93%, 2 years – 88%, 3 years – 84%.

Salehrabi (2004) –

This study evaluated the 8-year outcome of over 1.4 million conventional root canal cases performed by both general dentists and endodontists (root canal specialists).

Just like with the other studies above, the data evaluated came from a dental insurance database. And endodontic failure was defined as the tooth requiring some type of endodontic retreatment or extraction at a later date.

▲ Section references – Chen, Raedel, Salehrabi

Why did these studies only evaluate 3, 5, and 8-year periods?

- One of the findings of the Salehrabi study above was that when further treatment was required (either retreatment or extraction), 88% of those procedures were performed within the first 3 years following their tooth’s original root canal work.

That suggests that even the shortest study discussed above completely encompassed the most important time frame to evaluate.

- Another consideration is that with longer-term studies, additional pathologies (like gum disease) become an ever-increasing factor in the survival of the tooth.

And since insurance databases only document events (like pulling teeth) and not the reason for them, the ability to accurately estimate failure rates over a long duration seems questionable.

2) Comparing the success of RCT performed by general dentists vs. endodontists.

It seems logical to speculate that the extra training a root canal specialist receives positively influences the outcome of their work. Research seems to confirm this:

- Background information included in a paper by Iqbal states that success rates for root canal work performed by general dentists run on the order of 65% to 75%. Whereas for specialists, this number lies around 90%.

- A small study involving just 350 teeth conducted by Alley found a success rate of 98% for therapy performed by endodontists vs. 90% for cases completed by general practitioners.

More evidence, a different spin.

A study by Lazarski evaluated the outcome of over 100,000 root canal cases (each tooth was followed over a minimum time frame of 2 years).

It reported a similar success rate for work completed by both specialists and general dentists.

But it also noted that the specialist group treated a substantially greater percentage of molars (multi-rooted teeth often having a very complex root canal system), whereas the generalist group more single-rooted, typically easier to treat, teeth. (See our “failure rate by tooth type” table below for a comparison.)

- The similar success rate achieved by specialists while treating more difficult cases suggests that the extra training and experience they have plays a valuable role in treatment outcomes.

- But this extra experience may not be needed for simple cases.

▲ Section references – Iqbal, Alley, Lazarski

3) Incidence of root canal failure by tooth type.

We ran across three studies that included data about endodontic failure by tooth type.

Iqbal (2007) –

As a part of its evaluation of 90 failed root canal cases, this study reported the following failure rates:

| Distribution of failed root canals by tooth type. | |

|---|---|

| 4.4% of cases … | Upper incisors |

| 3.3% of cases … | Upper canines (eyeteeth) |

| 15.5% of cases … | Upper premolars (bicuspids) |

| 44.4% of cases … | Upper molars |

| 5.5% of cases … | Lower incisors |

| 1.1% of cases … | Lower canines |

| 5.5% of cases … | Lower premolars | 20.0% of cases … | Lower molars |

Burry (2016) –

As a part of its investigation of an insurance database, this study evaluated groups of teeth that had been treated by general dentists that had since experienced root canal failure (those that had developed problems at 1, 5, and 10 years after completion, over 338,000 teeth total). The failure rate per tooth type was similar for all three groups.

| Distribution of failed root canals by tooth type. | |

|---|---|

| 19% to 20% of cases … | Incisors and Canines |

| 32% to 34% of cases … | Premolars |

| 46% to 47% of cases … | Molars |

Hoen (2002) –

This study evaluated 337 teeth whose initial root canal treatment had failed.

| Distribution of failed root canals by tooth type. | |

|---|---|

| 20% of cases … | Incisors and Canines |

| 22% of cases … | Premolars |

| 58% of cases … | Molars |

Discussion.

- Anterior teeth (incisors and canines) tend to experience failure less often than premolars and molars.

- Teeth that most frequently have a single root canal (incisors, canines, lower premolars) tend to have the lowest failure rates.

- Teeth frequently/typically having multiple canals (upper premolars, upper molars, lower molars) tend to have the highest percentage of failures.

- Molars in general, and possibly upper molars in particular (the type of tooth typically having the greatest number of canals, which is 3 or more), have the highest failure rate by far.

(Not only does a larger number of canals present greater challenges but many additional canals are small and curved, thus making them difficult to both identify and treat.)

▲ Section references – Iqbal, Burry, Hoen

C) Retreating failed RCT cases.

What can be done for a tooth whose root canal treatment has been unsuccessful?

If your dentist determines that your tooth’s primary (initial) endodontic therapy has failed, you only have two options. They are …

1) Make an attempt to salvage your tooth.

This approach involves performing some type of endodontic retreatment procedure.

The rationale.

Since the underlying problem that currently exists with your tooth is that its root canal system is contaminated (with microorganisms, debris, irritants, etc…), the only dental procedure that can remedy its situation is additional root canal therapy (retreatment).

2) Have the tooth extracted.

If conditions within the tooth’s root canal system can’t be, or won’t be, resolved by performing some type of retreatment procedure, then the only other way to rid your body of the problematic conditions associated with it is to have it taken out.

Of course, ideal treatment would normally include replacing the tooth with an artificial one.

3) Not seeking treatment is not a valid option.

As an FYI point, due to the unpredictable nature of teeth that harbor infection, not making a decision about which approach will be pursued leaves you at perpetual risk for the development of complications.

If a tooth has no potential to be a healthy contributing member of your dentition (set of teeth), it should be removed before its condition affects surrounding tissues, neighboring teeth, or causes an emergency situation.

What treatment options exist for failed root canal treatment?

Your dentist generally has four basic approaches that they can offer as a solution for your tooth’s failed root canal status. Three of them involve performing some type of endodontic retreatment procedure.

- Conventional retreatment – This is the situation where the tooth’s root canal therapy is performed again, much like it was the first time.

In more formal terms, this approach is referred to as orthograde or non-surgical endodontic retreatment.

- Surgical retreatment – This option involves performing a minor surgical procedure where the tip of the problematic tooth’s root is accessed and corrections/improvements are made with it.

The formal term for this type of work is apical surgery. (FYI: The tip portion of a root is referred to as its “apex.”)

- Extraction with replantation – This procedure, as strange as it seems, involves extracting the problematic tooth. Then, some type of endodontic procedure is performed as a remedy for its failed endodontic status (like apical surgery). The repaired tooth is then placed back into its socket to heal.

The formal term for this procedure is intentional replantation.

- Extracting the tooth – Since retaining a tooth that shows evidence of pathology without performing some type of corrective procedure doesn’t make an appropriate choice, its extraction is indicated.

Afterward, ideal treatment usually involves replacing the missing tooth with some type of artificial one, like an implant or via dental bridge placement.

▲ Section references – Ingle, Hargreaves

Which option should be used?

Root canal vs. implant placement.

Note: The success-rate statistics stated in the discussion on that page are in reference to primary (initial) root canal work. As you’ll read below, retreatment cases may offer a lower success rate, and this difference must be kept in mind.

Possible retreatment approaches –

A) Non-surgical endodontic retreatment.

(Conventional retreatment.)

What does it entail?

This process involves repeating the same basic procedure (termed orthograde endodontic therapy The steps.) that was performed for your tooth originally, with the exception that additional effort will be required to remove the previously placed root canal filling materials.

Conventional / Orthograde retreatment.

Non-surgical retreatment is performed via an opening in the crown of the tooth.

A decision to proceed with this option simply depends on your dentist’s judgment about its chances for success.

Why is this approach usually the preferred one?

Most root canal failures are due to microorganisms living within the tooth’s root canal system. (They either survived the tooth’s primary treatment or invaded its filled root canal space after its work had been completed.) (Friedman)

- Since orthograde endodontic therapy offers the least restricted access to the tooth’s entire root canal system (which is needed in order to thoroughly disinfect and seal off the tooth’s interior space), it makes the preferred choice.

- Additionally, its non-surgical nature makes it the least aggressive option (in terms of creating tissue trauma, patient tolerance for the procedure, etc…).

▲ Section references – Ingle

When isn’t conventional retreatment chosen?

a) Difficulties with accessing the tooth’s root canal system.

In order to perform retreatment work, the dentist must be able to make access to the tooth’s root canal space. And in some situations, this may be difficult to achieve due to the manner in which the tooth was rebuilt following its original treatment.

As an example, the tooth may have required post placement in one of its canals. Why? (See picture of a post below.) In some cases, post removal can prove challenging (difficult to accomplish, doing so may place the root at risk for fracture).

b) Difficulties in instrumenting the tooth’s individual root canals.

If some type of situation exists that prevents the dentist from being able to use their instruments (mainly root canal files How they’re used.) throughout all regions of the tooth’s root canal space, the chances of retreatment success are reduced.

- A tooth may have anatomical issues that impede the dentist’s efforts, like canals that have an extreme curvature, heavy calcification, are exceptionally tiny in size and narrow in width, etc… (These issues may be the same ones associated with the original work’s failure.)

- Previously treated teeth may now be found to have issues associated with procedural errors or mishaps that occurred when performing that original work.

This can include obstacles that are now present, like broken files or clogged canals. Or unfavorable changes in canal geometry (intra-canal ledges, irregular/inappropriate canal enlargement, root perforations, etc…).

- In some cases, the type of material used to fill in and seal the tooth’s canals during its previous work may be difficult to remove.

▲ Section references – Ingle, Hoen

Success rates for conventional (non-surgical) endodontic retreatment.

As an example of what might be expected, a study by Gorni evaluated the 2-year outcome of 452 retreated teeth.

- It found that cases that posed what the investigators categorized as relatively straightforward retreatment challenges were found to have an 87% success rate.

- Those categorized as posing a higher level of difficulty (specifically, unfavorable changes in their original root canal anatomy caused by their previous work), were found to have just a 47% rate of success.

Note: The wide range of treatment outcomes determined by this study simply demonstrates the importance of your dentist’s abilities in creating a successful retreatment outcome.

- They must be able to form a valid opinion about what went wrong with the tooth’s original work.

- Understand how the tooth’s previous work may affect their retreatment attempts.

- And have the skills needed to be able to successfully overcome the difficulties that they expect to encounter.

Is referral to a specialist needed?

In some instances, the level of skill and expertise needed to perform conventional root canal retreatment may lie beyond what your dentist feels they can offer. If so, the services of an endodontist (root canal specialist) will be required.

We discuss some of the considerations associated with making this decision here: General dentist vs. Endodontist. Which to choose? We discuss endodontic retreatment costs here Procedure fees..

B) Surgical retreatment (Apicoectomy / Endodontic surgery).

Background.

As mentioned above, most cases of root canal therapy failure are due to microorganisms harbored within the tooth’s root canal system.

And as they, and the waste products they create, leak out of the tooth’s root the surrounding tissues are perpetually irritated.

a) With non-surgical endodontic retreatment …

The focus of the procedure is on disinfection. It is an attempt to eliminate the offending agents from within the tooth (then followed by filling in and sealing off this now re-cleansed space).

b) With surgical retreatment …

Surgical endodontic retreatment.

Apical surgery has been performed, including retrograde filling placement.

- One goal may be irritant containment.

The procedure is used to create a better seal of the root’s canal opening (often by placing a filling), so the irritating substances still harbored inside the tooth can’t leak out and continue to irritate the surrounding tissues.

- Another goal can be removing locations harboring infection.

This can include scraping away the tissues that have been affected by the disease process occurring around the root’s tip. Or trimming away parts of the root itself that contain portions of its canal(s) that can’t be properly cleaned.

When is a surgical retreatment approach needed?

Generally, the use of a surgical procedure is indicated when there is some reason why conventional (orthograde) root canal therapy would not be expected to be successful.

This might be due to complications associated with the tooth’s original root canal anatomy or ways it has been altered by previous treatment attempts. Or the dentist’s access to the canals via a conventional approach is impeded (like with the post example given above, see picture).

What does the procedure entail?

Accessing a tooth’s root requires a (minor) surgical procedure. Related to the fact that it’s just the tooth’s root tip (its apex) that’s accessed and treated, this procedure is frequently referred to as apical surgery or an apicoectomy.

Apicoectomy / Apicoectomy with retrograde filling – The steps.

In brief …

An incision is made in the gum tissue in the region of the root’s end, and it is flapped back. Bone tissue is then trimmed away, to the extent that the tooth’s root tip (apex) is revealed.

At this point, the precise steps that are carried out will vary according to the needs of the case.

- The apex of the root may be trimmed away (termed root-end resection). The amount is often on the order of 1/8th of an inch or so but varies according to the precise needs of the case.

The goal of the trimming may be to remove a problematic portion of the canal’s anatomy, or to provide a suitable site to place a filling (or both). Doing so also allows the dentist an opportunity to evaluate the canal’s seal that was created by its previous treatment.

- The diseased tissues that surround the root’s tip are scraped away (along with the microorganisms and debris they contain).

- In some cases, root canal treatment may be performed for the exposed root, in an attempt to remove the bacteria and irritants harbored in it as best as possible. (Performing root canal treatment via its root end is termed “retrograde” endodontic therapy.)

- A filling (termed a “retrograde” filling) may be placed in the root’s end, so to create an improved seal for its exposed root canal opening.

Once all of the needed steps have been performed, the surgical site is closed and stitches are placed to stabilize the gum tissue during the healing process that follows.

How extensive is the process?

This procedure is generally categorized as minor dental surgery. It falls on the same order as having a medium-sized tooth extracted, or gum surgery performed in an isolated area.

Some general dentists may feel that providing this procedure lies beyond their level of skill and training. If so, referral to an endodontist is indicated.

Success rates.

Research studies suggest that success rates for surgical retreatment cases range from 62% to 98% (Ingle).

▲ Section references – Ingle

Non-surgical retreatment may be needed first.

Your dentist may feel that performing orthograde (conventional) retreatment prior to your apical surgery will benefit your case’s outcome.

▲ Section references – Ingle

C) Tooth removal, retreatment, and replantation.

This option is usually referred to as “intentional replantation.”

What does this procedure involve?

As you might deduce from this section’s title, this procedure is composed of the following steps:

- The tooth is extracted. – This step must be performed as gently as possible because doing so helps to ensure that the tissues attached to the tooth’s root surface (that will be important in promoting its reattachment during the healing process) aren’t excessively traumatized.

- Some kind of endodontic retreatment procedure is performed. – This is usually some type of step similar to what is performed during apical surgery (discussed above).

Since most endodontic failures are associated with microorganisms inside the tooth, retrograde endodontic therapy (root canal retreatment performed from the root end of the tooth), is common, as is retrograde filling placement.

The care the dentist takes in handling the tooth is vital in preserving the tissues attached to its roots(s). For example, the tooth must be kept moist at all times. Touching its root surfaces avoided. Procedure time is ideally kept to 15 minutes or less.

- The tooth is then gently replanted back into its socket. – Some type of splinting will be required to stabilize the tooth during the next 7 to 14 days of its healing process.

When is intentional replantation considered?

This technique is generally only utilized in cases where conventional or surgical retreatment (both described above) is not feasible.

For example, intentional replantation might make the better choice for a tooth whose root tip lies in close proximity to a major nerve that might be damaged during apical surgery.

Success rates.

▲ Section references – Ingle

Complications.

A problem sometimes associated with intentional replantation is progressive root resorption (the loss of root structure due to bodily processes).

The potential for the tooth to experience this complication generally correlates with procedural factors, such as how gently it was extracted, how it was handled and maintained while out of the mouth, and for how long.

▲ Section references – Ingle

D) Tooth extraction.

Besides performing some type of case retreatment, the only other appropriate choice for a tooth whose root canal work has failed is to extract it. This option might be the only one suitable for cases where retreating the tooth is not possible, or only offers a low probability of success.

- Extraction, without tooth replacement. – While just removing the tooth may seem the simplest and cheapest solution, doing so usually makes the poorest choice. Here’s why. Your dental health is best preserved by replacing missing teeth.

- Extraction, with tooth replacement. – This link leads to our discussion about different tooth replacement options and associated costs. Possible alternatives.

And since it’s become such a common alternative to having endodontic therapy in general, this link discusses considerations associated with root canal treatment vs. dental implant placement. Factors in deciding.

Timing your next step.

Whatever decision is made, your corrective treatment should be performed within the time guidelines recommended by your dentist.

Following their examination, they can gauge how much urgency appears to be involved. As a precaution, your dentist might write you a prescription for antibiotics so you already have it on hand if conditions with your tooth worsen before your definitive treatment can be performed.

Why you mustn’t delay.

- Teeth that have failed endodontic treatment are unpredictable due to the fact that they typically harbor infection, which has the potential to flare up (create pain and/or swelling), possibly significantly so, without warning.

- Infections that are allowed to persist can result in complications associated with the tissues that surround the problem tooth (possibly even affecting neighboring teeth). Also, teeth that harbor chronic endodontic infections can be more problematic to successfully retreat.

What’s next?

We have lots more information about difficulties with root-canalled teeth.

Page references sources:

Alley B, et al. A comparison of survival of teeth following endodontic treatment performed by general dentists or by specialists.

Burry JC, et al. Outcomes of Primary Endodontic Therapy Provided by Endodontic Specialists Compared with Other Providers.

Chen SC, et al. An epidemiologic study of tooth retention after nonsurgical endodontic treatment in a large population in Taiwan.

Friedman S. Considerations and concepts of case selection in the management of post-treatment endodontic disease (treatment failure).

Gorni FG, et al. The outcome of endodontic retreatment: a 2-yr follow-up.

Hargreaves KM, et al. Cohen’s Pathway of the pulp. Chapter: Nonsurgical retreatment.

Hoen MM, et al. Contemporary Endodontic Retreatments: An Analysis based on Clinical Treatment Findings.

Ingle JI, et al. Ingle’s Endodontics. Chapter: Retreatment of Non-Healing Endodontic Therapy and Management of Mishaps

Iqbal A. The Factors Responsible for Endodontic Treatment Failure in the Permanent Dentitions of the Patients.

Iqbal M, et al. An Investigation Into Differential Diagnosis of Pulp and Periapical Pain: A PennEndo Database Study.

Lazarski MP, et al. Epidemiological evaluation of the outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment in a large cohort of insured dental patients.

Raedel M, et al. Three-year outcomes of root canal treatment: Mining an insurance database.

Ricucci D, et al. Fate of the tissue in lateral canals and apical ramifications in response to pathologic conditions and treatment procedures.

Salehrabi R, et al. Endodontic Treatment Outcomes in a Large Patient Population in the USA: An Epidemiological Study.

Tabassum S, et al. Failure of endodontic treatment: The usual suspects.

Torabinejad M, et al. Endodontics. Principles and Practice. Chapter: Longitudinal tooth fractures.

All reference sources for topic Root Canals.