How X-rays are used to diagnose the need for root canal treatment.

How dentists use X-rays to determine if a tooth needs root canal treatment.

One of the most valuable tools that a dentist has in diagnosing a tooth’s endodontic status is an X-ray examination.

In fact, it’s unlikely that any tooth thought to possibly need root canal treatment could be evaluated properly without taking at least some (probably two or more) conventional dental radiographs. And for especially problematic cases, 3-dimensional (3D) imaging may prove to be indispensable.

This page shows what your dentist looks for when they read X-rays.

With today’s digital radiography, it’s pretty common that a dental patient will get a chance to see the X-rays that have been taken of their tooth. Usually, they’re shown to them right there on the dentist’s chairside computer monitor.

So, if you do get a chance to see your films, this page gives examples of what your dentist looks for as they formulate an opinion about whether or not your tooth shows signs of infection or other developing pathology that indicates that it will require endodontic therapy.

Signs found on dental X-rays that diagnose a tooth’s need for root canal treatment.

As a dentist examines their patient’s radiographs, they’ll look for specific details that if seen on the image can be important clues about the tooth’s health.

What exactly does the dentist look for?

For the most part, the signs they’re searching for are ways the X-rayed tooth’s image deviates from what’s expected with a normal healthy tooth.

- Sometimes these changes are extremely minute and therefore, unfortunately, open to interpretation. (This is especially true with root canal cases involving inflamed tissues, or early or very low-grade infection.)

- At other times, the signs that are seen are so obvious that they offer a slam dunk when it comes to making the diagnosis that root canal therapy is needed. (This can be especially true in cases involving chronic (long-standing) tooth infection.)

Specific signs that a dentist looks for when reading a tooth’s X-rays.

a) Periapical radiolucencies.

One of the most diagnostic signs that a dentist will see on an X-ray that strongly suggests that the tooth will require endodontic therapy is finding a dark area centered at its root tip.

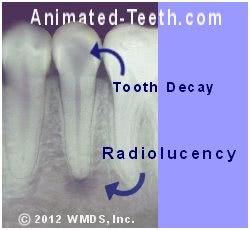

X-ray showing a periapical radiolucency due to root canal system infection.

The presence of both tooth decay and a radiolucency is strong evidence that endodontic treatment is needed.

- This kind of dark spot on an X-ray is referred to as a “radiolucency.”

- A radiolucency centered on the tip of a tooth’s root (like shown in our picture) is referred to as a periapical radiolucency. (The term “periapical” refers to the fact that the lesion is located at the tip of the tooth’s root, its apex.)

- In terms of shape, the lesion frequently has a “hanging drop” appearance.

What does the presence of a periapical radiolucency signal?

The dark spot is an indication that something has triggered a change in the density (hardness) of the bone in that area.

In the case of endodontic pathology due to infection:

- It’s a sign of infection located in the nerve space inside the tooth (pulp chamber, root canals).

- As byproducts of the infection leak out of the tooth (via the opening at the tip of the root where the tooth’s nerve used to enter), they trigger an inflammatory response in the surrounding tissue.

- As part of this response, bone tissue is sacrificed (eroded away) in the area immediately surrounding the point of exit from the tooth. And it’s this change in bone density that causes the dark spot to appear on the X-ray.

- As the lesion develops, it fills with immune system cells whose purpose is to defend against the irritating infection byproducts leaking out of the tooth.

(In essence, the formation of an endodontic periapical radiolucency is evidence of the person’s body creating a line of defense against the further spread of bacteria and infection byproducts from its associated tooth.)

▲ Section references – Hargreaves

The specific type of lesion associated with the radiolucency might be apical periodontitis, an apical granuloma, an acute apical abscess (abscessed tooth), or a radicular cyst.

Additional details about radiolucencies associated with endodontic pathology.

Why isn’t a radiolucency always seen on an X-ray of a tooth that needs root canal therapy?

A tooth can have advanced endodontic pathology but when an X-ray is taken of it, everything about it and its surrounding tissues appears normal and healthy.

This conundrum is easy enough to explain:

- The bone tissue changes that show up on a radiograph take time to develop (see below for further details).

So it may be that other signs and symptoms have developed that have warranted an investigation of the tooth. But radiographically it’s simply too early to observe any indication of its developing condition.

- It may be that due to the nature of the tooth’s condition (including low virility) whatever associated changes have occurred are so minute that they’re not readily detectable.

It’s suggested that only about 55 to 65% of root canal cases that are initiated due to pulpitis (a state where the tooth’s nerve tissue is still alive but inflamed) show a periapical radiolucency when their diagnosis for endodontic therapy is made.

▲ Section references – Mortazavi

Why does an X-ray show a dark spot?

As alluded to above, a radiolucency shows up on an X-ray because the bone in that region is less dense (it contains less mineral content, or else there is an actual void in the bone tissue in that area).

When dental X-rays are taken:

- Areas having higher density show as white regions (referred to as radiopacities). That’s because the density of the object blocks the X-rays, and as a result that part of the X-ray film/sensor is shielded and remains unexposed, thus the object appears white or light in color.

- In areas having lower density, the X-ray beam passes through the structure easily, thus exposing/triggering the X-ray film/sensor. As a result, that portion of the picture appears darkened (referred to as radiolucent areas).

When will a radiolucency (bone changes) show on an X-ray?

Before a developing lesion will show up as a dark spot on a radiograph, the bone in the affected area must have finally reached a point where at minimum around 7% of its mineral content has been lost, and possibly as much as 30 to 50%, depending on the type of bone (cancellous vs. more dense cortical bone) that exists in the affected area.

And because it takes time for this level of change to occur, X-rays taken early on during a nerve’s demise may not reveal any noticeable signs, and thus not assist with the tooth’s diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis – Other reasons for apical radiolucencies.

Unfortunately, not all radiolucencies are simple to interpret.

Easy cases.

On the X-ray above, a large cavity in the tooth is obvious. So, between the two (the deep cavity and the radiolucency at the tip of the tooth’s root, which equates with cause and effect), the dentist can feel essentially 100% confident that a diagnosis for root canal treatment is accurate.

But other “dark spots” discovered in images are much more difficult to interpret.

Confusion with previously treated teeth.

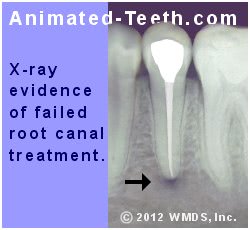

Since failed root canal treatment Signs | Symptoms is typically associated with the presence of persistent inflammation due to infection harbored within the tooth, when failure has occurred, a radiolucency can be expected to be present too.

A periapical radiolucency associated with failed root endodontic therapy.

But discovering a dark spot on an X-ray doesn’t necessarily mean that a problem exists. There can be other explanations too.

For example, it may be that the tooth’s original pre-treatment lesion simply hasn’t fully healed yet. Or possibly what is seen is scar tissue (healthy remnants of the original lesion that are still present).

Confusion with healthy teeth.

Further complicating the interpretation of X-rays is the fact that some radiolucencies associated with teeth are due to totally benign conditions and therefore require no attention at all.

Of course, all of this potential for misdiagnosis simply means that to make an accurate determination, additional types of testing and evaluation Methods used. must be performed by the dentist too. Taking X-rays alone won’t suffice.

b) Other visible changes on X-rays that may indicate that a tooth has endodontic problems.

Background.

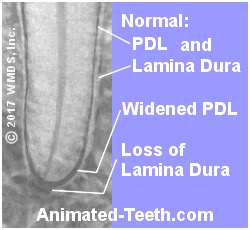

Every tooth is held in place by a ligament that surrounds its root. This is referred to as the tooth’s periodontal ligament or “PDL”.

Any radiographic changes that take place within the space that the PDL occupies, or the adjacent bone to which it attaches, can be a sign of nerve problems within the tooth and a need for root canal treatment.

1) Widening of the periodontal ligament space.

If a portion of the PDL space shows signs of widening, it may be an indication of developing nerve tissue pathology.

Changes with the PDL space and Lamina Dura suggest that a root canal is needed.

When endodontic problems are involved, this space becomes wider as it fills with exudates (fluid byproducts) created by the state of inflammation that exists with the pulp tissue (nerve) inside the tooth.

Differential diagnosis.

As a point of concern for the dentist, other causes can explain PDL widening.

One of these is as simple as a tooth that has increased mobility, like that that can result from tooth clenching. (This habit can also cause tooth sensitivity, which might also be misdiagnosed as a symptom indicating the need to perform endodontic therapy.)

2) Changes in the lamina dura.

The surface layer of the bony socket that encases a tooth’s root, and to which its periodontal ligament is attached, shows as a white outline on dental X-rays.

This layer of dense bone is referred to as the lamina dura. And when portions of it on an X-ray appear less evident or else thickened, it can be a sign of the bone’s response to the degeneration of the tooth’s nerve that’s underway. (See picture above.)

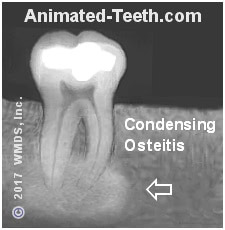

3) Condensing osteitis.

Chronic inflammation associated with pulpal pathology can trigger a response where additional bone is deposited in the area surrounding a tooth. This is referred to as condensing osteitis.

Since this region now has increased density (more bone tissue has been deposited), it appears as a diffuse white (radiopaque) region on X-rays. It’s generally centered in the region of the tip of the tooth’s root(s).

Our picture shows such an instance. The source of the tooth’s irritation is a deep filling that comes close to its nerve.

These are the early signals.

The changes just described are the first signs of developing pulpal pathology. And they’re more commonly seen on X-rays than a fully mature periapical radiolucency as described initially on this page.

A paper by Mortazavi states that regarding radiographic evidence:

- PDL widening is the most common finding associated with endodontic pathology, being present in 46% of cases.

- Identifying changes in the lamina dura is the second most common finding. 20% of cases show a loss and 18% thickening.

- Evidence of condensing osteitis is present in 12% of cases.

▲ Section references – Mortazavi

X-rays often show an obvious cause for the tooth’s endodontic problems.

While not necessarily indicative on its own, identifying some type of obvious tooth-related pathology on an X-ray makes it that much easier for a dentist to be confident in their diagnosis.

Radiographs of teeth that require root canal treatment frequently reveal the presence of large cavities, periodontal problems (gum disease), the presence of large deep fillings, or obvious problems with the way previous endodontic treatment was performed. Failure reasons.

Identifying these types of conditions helps the dentist to complete their diagnostic picture because both cause and effect are evident on the X-ray.

That’s an important aid.

We’ve brought this point up because it’s been shown that a dentist’s ability to accurately diagnose a tooth’s need for root canal treatment, based solely on the minute changes they’ve visualized on their patient’s X-rays, is questionable.

That’s because reading radiographs can be highly subjective. This point was documented in a study by Goldman that evaluated dentists’ interpretation of the same set of films. It determined that:

- The dentists’ diagnosis was only in agreement 50% of the time.

- When the same set of films was shown to each dentist several months later, they only concurred with their original diagnosis in 72 to 88% of cases.

So clearly, it’s important for a dentist to corroborate what they feel they have seen on their patient’s X-rays with other clinical observations and testing.

▲ Section references – Goldman

Example case: X-ray evaluation of a tooth’s root canal treatment (before and after).

The picture below shows a series of X-rays of a tooth that required and subsequently received endodontic therapy. However, its initial treatment ultimately failed.

The following legend points out the kinds of radiographic changes that a dentist looks for when evaluating a tooth’s current endodontic status.

The before X-ray – This pre-treatment X-ray of the tooth shows that it has a large cavity in its crown (the chewing part of the tooth). The decay has advanced to the tooth’s nerve space (pulp chamber and root canal system).

At this point, the tooth’s nerve has died and its root canal space has become infected. The periapical radiolucency that has formed at the tooth’s tip is evidence of this.

X-rays of before and after root canal treatment. Radiographic signs of root canal failure.

The after X-ray – This image documents the status of the tooth’s root canal treatment many months after it was completed. The periapical radiolucency seen in the “before” picture has disappeared due to bone tissue healing.

[The tooth’s root canal space has a lighter color in the “after” X-ray. That’s evidence of the filling compound (gutta-percha) that’s been packed inside the tooth during its endodontic therapy. It fills in and seals off the tooth’s nerve space.]

Failed treatment X-ray – This last X-ray, taken 2 years later, shows that a periapical radiolucency has reformed, suggesting that the tooth’s root canal space has become reinfected.

This kind of root canal treatment failure can be a result of

coronal leakage. What is this?

Additional details about X-rays used to diagnose endodontic conditions.

What type of X-ray is needed?

The kind of X-rays that dentists take when evaluating a tooth for endodontic problems are referred to as periapical radiographs.

The term “periapical” refers to the fact that the picture shows the entire tooth, especially its entire root portion (the term “apical” specifically refers to the “tip of the root”). All of the radiographic images on this page are periapicals.

Actually, it’s not just seeing the tip of the root that’s important. A portion of the surrounding bone tissue (along the lines of 1/4 inch or so surrounding the tooth) must also be visible in the image for it to be of diagnostic quality.

How many X-rays of your tooth will be needed?

When diagnosing the possible need for endodontic therapy, your dentist will probably end up taking at least two pictures of your tooth, possibly more. Each one will be taken from a slightly different angle.

Beyond the second picture just allowing the dentist a chance for a “second opinion,” the change in angle helps them determine if what they see in the picture is truly associated with the tooth in question.

Digital vs. film X-rays.

Just as advances have been made in photography, similar changes have taken place with dental radiography too. Whereas historically X-ray pictures were only taken using (“old fashion”) film, nowadays your dentist may use a digital sensor instead.

Neither is better. One is more convenient.

There is no overwhelming body of evidence that supports the notion that one method is superior to the other in terms of being more diagnostic. Having said that, digital X-rays do offer some advantages and options that conventional films cannot.

- Since no developing process is involved, digital X-rays can be viewed immediately after they’re taken.

- Digital X-rays offer the option of image manipulation (changing contrast levels, color enhancement, reverse imaging, image subtraction, etc…), although this ability doesn’t necessarily result in more accurate image interpretation.

- Digital X-rays are more precisely duplicated and sent electronically.

So if your dentist still only takes traditional radiographs, it doesn’t mean that you aren’t in good hands.

Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT)

Beyond just routine two-dimensional intraoral radiography (the standard 2D X-rays that all dentists take), a more advanced form of radiographic evaluation involves the use of cone beam computed tomography (a dental CT scan).

This technique creates a 3D representation of your tooth and associated structures so they can be evaluated in greater detail (via cross-sections that show the tooth and its surrounding bone sectioned at varying angles). However, due to the expense of the needed equipment, it’s more common to find this type of imaging being used in the offices of root canal specialists Endodontists. as opposed to your general dentist.

Uses for CBCT radiography.

a) Case diagnosis.

While a tooth’s condition should initially be investigated using traditional (2D) radiography, in some instances, like when evaluating difficult to diagnose cases, the additional information gained from 3D imaging may provide significant benefit.

As an example, a study by Uraba found that when evaluating teeth that due to anatomical considerations are characteristically more difficult to examine radiographically (upper incisors, canines, and molars), the use of CBCT was able to identify signs of an endodontic problem (periapical lesions, see pictures above) in 20% more cases.

b) Preoperative case planning.

CBCT imaging may be useful in evaluating a tooth’s root canal space on a pre-op basis. Especially if other types of X-ray evaluation have suggested that the configuration of the tooth’s root canal system displays anomalies that might complicate its treatment.

Generally speaking, however, CBCT evaluation should only be considered for cases where there is a good reason to expect that the increased detail that it can provide is actually needed. It is not a technique that should be used routinely for cases.

c) During treatment.

During the course of performing a tooth’s endodontic therapy, difficulties may crop up that CBCT evaluation may be able to help clarify and resolve.

Obviously, this can aid in treatment success. But the use of 3D imaging might also assist the dentist in completing the tooth’s procedure in a more conservative fashion. (For example, the openings of additional canals might be located radiographically, as opposed to the dentist needing to search for them blindly by progressively trimming away more and more of the tooth.

d) Postoperatively.

Post-procedure use of CBCT imaging might be the only way to accurately diagnose post-treatment complications such as overlooked canals or root cracks.

CBCT imaging should be reserved for special situations.

As useful as 3D technology can be, performing a scan exposes the patient to a higher level of radiation than when the conventional 2D X-ray technique is used. There is also the issue of its added expense.

In light of this, the current recommendation of several prominent organizations (American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, American Association of Endodontists, and European Society of Endodontology) is that its use should be considered to be an adjunct to conventional low-dose dental radiography (traditional two-dimensional dental X-rays).

The latter two organizations have position statements that emphasize that the use of CBCT radiography should not be routine but instead only used for cases where important factors justify its use and the cost-effectiveness for the patient has been taken into consideration.

▲ Section references – Parirokh

What’s next?

Here’s more details about root canal treatment.

Page references sources:

Bender IB. Factors influencing the radiographic appearance of bony lesions.

Goldman M, et al. Reliability of radiographic interpretations.

Hargreaves KM, et al. Cohen’s Pathway of the pulp. Chapter: Pathology of the periapex.

Ingle JI, et al. Ingle’s Endodontics. Chapter: Diagnostic Imaging

Mortazavi H, et al. Review of common conditions associated with periodontal ligament widening.

Parirokh M, et. al. Treatment of a Maxillary Second Molar with One Buccal and Two Palatal Roots Confirmed with Cone-Beam Computed Tomography.

Uraba S, et al. Ability of Cone-beam Computed Tomography to Detect Periapical Lesions That Were Not Detected by Periapical Radiography: A Retrospective Assessment According to Tooth Group.

All reference sources for topic Root Canals.

Comments.

This section contains comments submitted in previous years. Many have been edited so to limit their scope to subjects discussed on this page.

Comment –

Are 3D X-rays really needed?

For my tooth’s root canal my dentist says that 3d X-rays are needed. It’s a pretty big added expense. It cost a lot too when they removed my son’s wisdom teeth. Can I skip this?

Wellington

Reply –

It’s not really possible for us to answer your question. Only the dentist treating you can really make that determination.

The position of several dental organizations listed above is that Cone Beam (3D) evaluation should never be performed routinely for root canal cases. The issue is not just the cost but also the increased exposure to radiation that the patient receives.

We have to assume that evaluation of your tooth began initially with some type of (routine/traditional) 2D X-ray exam. And when sharing those pictures with you, we would think that the dentist might have pointed out what they noticed on those films that suggests that there are anomalies in your tooth’s root canal system that indicated the need for 3D imaging to clarify. If they didn’t, you might ask.

Staff Dentist